The NFL’s First Game Was Played in Dayton

Here’s how America’s fall obsession took its initial steps in Dayton during the autumn of 1920 with a game between the Dayton Triangles and the Columbus Panhandles.

September 2014 Issue

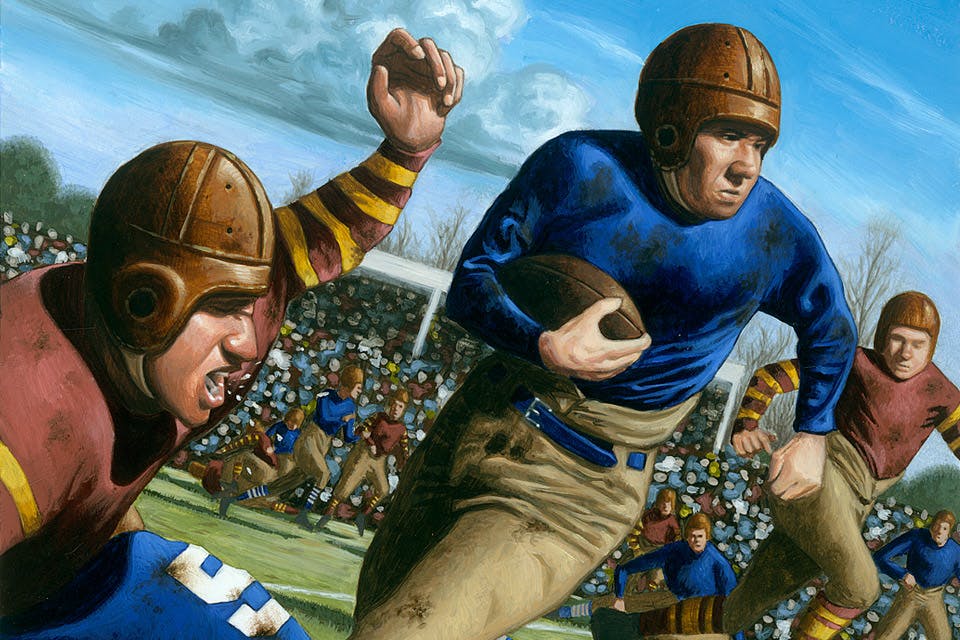

BY Leo DeLuca | Illustration by AG Ford

September 2014 Issue

BY Leo DeLuca | Illustration by AG Ford

Triangle Park roughly resembles its name. Bordered by the Stillwater River to the west and the Miami River to the east, the downtown Dayton green space was surrounded by a bustling city during the early years of the 20th century.

Industrialists Edward Deeds and Charles Kettering bought the unusually shaped parcel from the estate of local jewelry entrepreneur Edwin Best in the spring of 1917. That previous autumn — just three and a half years after the Great Dayton Flood nearly decimated the city — the pair had sponsored a football team, offering a heavy-hearted community something to rally around.

Deeds’ and Kettering’s three conglomerated enterprises — Dayton Engineering Laboratories Co. (known as Delco), Dayton Metal Products Co. and the Domestic Engineering Co. — formed an industrial triangle downtown, which inspired both their football team’s name and the place it would call home.

Joining the Ohio League in 1916, the Triangles played their inaugural season home games at Westwood Field, before moving to their newly built facility along the riverfront the following year. Also used as a recreation site for Deeds’ and Kettering’s employees, a baseball diamond was included in the park’s design.

The nation’s love of football was but a blip in those days. Players worked day jobs in factories or freight yards, practicing a couple times each week and getting paid $50 a game on the weekends. In Dayton, players such as George “Hobby” Kinderdine, Francis Bacon and Lou Partlow happily supplemented their income by joining the Triangles football team.

Kinderdine — a Delco machine operator, night superintendent and general foreman — earned his nickname after sustaining an injury that caused him to hobble for a brief spell. The name stuck, and so did his reputation as one of the toughest centers and kickers of his day.

Delco manager and educational director Francis Bacon was a hearty halfback who arrived in Dayton by way of Indiana and played his first full season with the Triangles in 1919.

Lou Partlow, on the other hand, had been playing football in the area since 1913, earning the nickname the “West Carrollton Battering Ram” during his time with the West Carrollton Paper Co. team. He was often seen running through the woods near the Miami River, weaving in and out of the maze of trees, imagining them to be his opponents. On occasion, it’s said he would purposefully lower a shoulder into a sizable trunk as a way to build up strength.

***

The Columbus Panhandles also played football in the Ohio League, although they’d been at it for a decade and a half longer than the Triangles. Organized in 1900, the team consisted of workers from the Pennsylvania Railroad Co.’s panhandle shop on the southeast side of Columbus. The blacksmiths, boilermakers, welders, painters and machinists who worked there spent long days repairing busted-down and beaten locomotives, earning meager wages while performing hard labor in hellish heat.

Near the turn of the 20th century, the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. created the Panhandle Athletic Club to offer its workers the opportunity to participate in sports ranging from boxing to baseball. But it was the club’s Columbus football team that immediately caught people’s attention. “One of the strongest noncollege teams to come forward this year is the Panhandle railroad team made up of big, hardy railroad men,” trumpeted the Columbus Press-Post in its Sept. 23, 1900, edition.

A football team filled with railroad workers also had financial advantages for Columbus Panhandles manager and future NFL president Joe Carr. Because most of his players were employees, the team could ride the rails for free to road games. The Columbus team also benefited from one of the hardest-hitting weapons in early football history: the Nesser brothers. With an 18-year age difference between the oldest and youngest, the six Nesser siblings — Ted, Al, Fred, Frank, Phil and John — were one of the country’s most fearsome and famous football families.

The brothers practiced football during their lunch breaks and were known for their toughness in a game where players frequently staggered to the sidelines dizzy and disoriented, sometimes with broken noses and loose teeth.

Renowned Notre Dame football player and coach Knute Rockne may have said it best when he once remarked, “Getting hit by a Nesser is like falling off a moving train.”

***

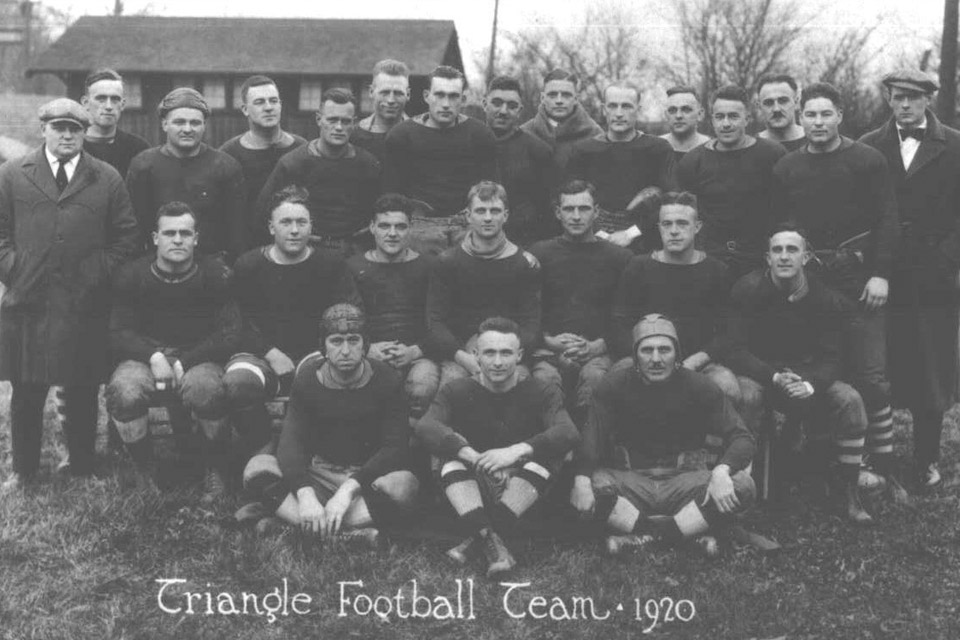

On Sept. 17, 1920, representatives from 11 franchises, including the Dayton Triangles, gathered at Canton Bulldogs owner Ralph Hay’s Hupmobile auto showroom to organize the framework for the first professional football league. Initially known as the American Professional Football Association, it was renamed the National Football League in 1922. (photo courtesy of Dayton History)

The roots of professional football stretch back to Nov. 12, 1892, when Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Athletic Association paid former Yale football star William “Pudge” Heffelfinger $500 to play in a single game. Allegheny won and profited $621, even after paying Heffelfinger’s then-staggering fee.

As professional football evolved throughout Pennsylvania and the Midwest in the years that followed, team owners began looking for ways to bring order to what had become an increasingly disorderly affair.

On Sept. 17, 1920, representatives from 11 franchises, including the Dayton Triangles, gathered at Canton Bulldogs owner Ralph Hay’s Hupmobile auto showroom to organize the framework for the first professional football league. Initially known as the American Professional Football Association (it was renamed the National Football League in 1922), the new consortium featured 14 teams, and its franchises stretched from Rock Island, Illinois, to Rochester, New York.

Along with the Triangles, Bulldogs and Columbus Panhandles, the association counted the Chicago Cardinals (now the Arizona Cardinals) and the Decatur Staleys (the team George “Papa Bear” Halas moved to Chicago and renamed the Bears in 1922) among its members.

In an effort to capitalize on the immense fame of Bulldogs star Jim Thorpe, who had won two gold medals in the 1912 summer Olympics and also played professional baseball, the new league elected him as its first president.

Most games would end up being played on Sunday afternoons following church, because many people had to work on Saturdays. Triangles manager Carl Storck and Panhandles manager Joe Carr, who were already acquaintances from their time in the Ohio League, scheduled their first game against each other.

That matchup — set for Sunday, Oct. 3, 1920, at 2:30 p.m. — just so happened to be the earliest-scheduled game of the American Professional Football Association’s inaugural season.

***

Oct. 3, 1920, was a warm day in Dayton, with temperatures reaching 75 degrees. A headline in the Dayton Daily News that morning read: “Governor Cox, Coming Sunday from 9,000-Mile Speaking Tour of West, to Find Friends Waiting.”

Inside the newspaper, P.A. Melton — a woman believed to be the oldest in Dayton at the time — was quoted as saying, “I’ve waited 95 years to vote, and now I’m going to cast my ballot for Governor Cox.” The ratification of the 19th amendment just a month and a half earlier had given women the right to vote. At the time, Ohio Gov. James M. Cox and his vice presidential running mate Franklin Delano Roosevelt were in the midst of a losing campaign against Warren G. Harding.

The day of Cox’s speech, football fans assembled at the 5,000-capacity Triangle Park to witness what is now considered the NFL’s first game. Blue Dayton jerseys lined one side of the field, while burgundy Columbus jerseys occupied the other. The players wore heavy canvas pants and leather helmets. Referee C.J. McCoy blew his whistle to mark the start of play.

Excitement filled the crowd as the Triangles reached the Panhandles 20-yard line early in the first quarter, but a fumble by Dayton’s Lou Partlow cost the team its first touchdown. From there, the game became a tug of war.

“In the second period it looked as though the Triangles were going to be scored upon,” the Dayton Herald reported in the following day’s newspaper. “With the ball on the Triangle 40-yard line, [Lee] Snoots broke away just as the head [line judge’s] whistle sounded. Many of the Triangles stopped in their tracks, but Snoots kept running and was downed about 10 yards from the goal.”

The Panhandles failed to score on that drive. Although they managed to hold Dayton scoreless through the first half of the game, a gripping moment in the third quarter finally turned the tide for the Triangles.

With Dayton near the center of the field, Partlow broke through the Panhandles’ line for a 40-yard run that put his team at the 10-yard line. Francis Bacon then reeled off a three-yard gain, before Partlow carried the ball over the goal line on the next play, scoring what is now recognized as the NFL’s first touchdown. Moments later, “Hobby” Kinderdine kicked the league’s first extra point, taking the Triangles into the fourth quarter with a 7–0 lead.

Try as they might to subdue the Triangles, the Panhandles could not rise to the occasion. While the Nesser name remained an attraction, the famous football brothers were largely past their prime. Al Nesser was up north playing for the Akron Professionals. Only Ted, Phil and Frank Nesser were on the Panhandles’ roster that day, and Frank was the only starter. The Panhandles’ 37-year-old head coach Ted Nesser, often considered the greatest of the Nesser brothers, did sub himself in for tackle Oscar Kuehner late in the game, but it was to no avail. When Frank Nesser punted the ball to the Triangles around the middle of the fourth quarter, Bacon sealed the win.

“Bacon made a brilliant dash of 40 yards through the entire Panhandle team, after grabbing one of Nesser’s punts,” the Dayton Daily News reported the following day in its recounting of the halfback’s touchdown run.

The fourth quarter ended with a final score of 14–0. As the hometown fans in attendance exited Triangle Park, none had any idea they had just witnessed the dawn of a new era in American sports.

***

A full crowd gathered at the 5,000-capacity Triangle Park (pictured above when there was no game going on) to witness what is now considered the NFL’s first matchup. Blue Dayton jerseys lined one side of the field, while burgundy Columbus jerseys occupied the other. (photo courtesy of Dayton History)

Many believed the Triangles were on their way to a championship title at the start of that 1920 season. On Oct. 20, the team nearly edged out Jim Thorpe and the Canton Bulldogs. But when Thorpe nailed a kick at the game’s end, the matchup finished as a 20–20 tie.

The Triangles played six games before the Akron Professionals handed the team its first loss on Nov. 21. The team ended up finishing with a respectable record of 5–2–2, while the Panhandles closed out their season at 2–6–2.

As the renamed National Football League expanded in the years that followed, it eventually became less focused on the Midwest. NFL president Joe Carr, who oversaw the league from 1921 until his death in 1939, realized he needed teams in bigger cities if professional football was going to flourish.

In 1923, the Columbus Panhandles became the Columbus Tigers, but the team eventually folded in 1926. Although the Triangles survived the 1920s, it became evident that Dayton was too small to support a team in the growing league. On July 12, 1930, fabled bootlegger Bill Dwyer bought the Triangles. He moved the franchise to Brooklyn and renamed it the Dodgers.

Today, Dayton’s Triangle Park serves as the city’s lasting reminder of its team. The wide-open expanse at the confluence of the Stillwater and Miami rivers is used for recreation, sporting events and community gatherings.

President Barack Obama stopped there during his 2012 re-election campaign. That same year, the original Triangles locker room was relocated to the nearby Carillon Historical Park, where it will eventually join other attractions in a larger exhibit devoted to Dayton sports history.

A lot has changed since that warm fall day when the National Football League first came to life here. The workaday whistle no longer calls the men who play the game back to long days on Delco machines or sweltering afternoons in panhandle shops. But on the field, the league remains a place of grit and sweat and sacrifice — one where the difference between success and failure is often a matter of inches and where greatness is everlasting.

Related Articles

Visit the William Howard Taft National Historic Site in Cincinnati

Our 27th president spent his formative years at this hilltop residence in a neighborhood built for the city’s social elite. Today, the restored home shares his story. READ MORE >>

Visit the William McKinley National Memorial in Canton

Our nation's 25th president is honored with an ornate monument that serves as his final resting place. An adjacent museum tells the story of his presidency and Stark County. READ MORE >>

Visit the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums in Fremont

Webb Hayes’ tribute to his parents at the northwest Ohio estate they called home was the nation’s first presidential library and museum. READ MORE >>