Ohio and the Election of 1920

The race introduced the world to Franklin D. Roosevelt, marked the first time women had the right to vote and pitted two Ohioans against one another for the White House

February 2015 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

February 2015 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

James M. Cox once said, “The Lord never gave me enough sense to sidestep anything.”

The comment was in reference to his campaign for governor of Ohio in 1916 — two years after he’d been voted out of the same office — but it held true in many facets of the Butler County native’s life. Cox, a former reporter for the Cincinnati Enquirer, bought Dayton’s struggling newspaper in 1898 and turned it into not only a profitable enterprise, but also a voice in the community.

He served two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives prior to being elected governor in 1912 and acquired a reputation as a reformer in a time when Ohio was rewriting its constitution. After being turned out two years later, he was re-elected in 1916 and again in 1918, becoming just the second man elected to three terms as governor of Ohio.

Around that time, President Woodrow Wilson was contemplating a third term, breaking the precedent of serving just two terms that had first been established by George Washington. But in October of that year, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke that led to his wife, Edith, effectively running the country while he recuperated. He was in no shape to run again, and by early 1920 everyone knew it. More than a few Democrats were willing to throw their name into contention.

“Nobody really knew who the standard bearer was,” says Mary Kay Mabe, an adjunct instructor of history at Sinclair Community College in Dayton and a researcher of James Cox. “There were so many people in the mix.”

So if the Democrats in the district he previously served as a U.S. congressman saw fit to suggest him as a potential nominee for president in an already crowded field in February 1920, Cox saw no reason to demur.

“The confidence of this group of men was given [to] me early in my start in public life,” he said when announcing his candidacy. “This confidence has remained with me throughout and this is a source of extreme gratification to me.”

***

In the years between the Civil War and World War I, Ohio became one of the most powerful states in the country as its population swelled — mostly in urban areas in northern Ohio — giving it increased sway in Congress and the Electoral College.

Many native Ohioans also returned home after serving in the Civil War to become public servants. In a 20-year span, three Ohioans — all Civil War veterans — were elected president: Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield and William McKinley. (Ulysses S. Grant and Benjamin Harrison were also Ohio-born Civil War veterans, but they lived in Illinois and Indiana, respectively, when they were elected to the presidency.)

Warren Gamaliel Harding was one of the volunteers who worked on McKinley’s 1896 front porch campaign in Canton. By then, he had already turned around the nearly bankrupt Marion Star after buying the newspaper with two friends in 1884, two years after he graduated from college.

Harding was elected state senator in 1898, served a term as lieutenant governor a few years later, and in 1914 became the first U.S. senator from Ohio elected by popular vote (prior to the passage of the 17th amendment in 1913, state legislatures chose senators).

Harding was a rising star in the national Republican Party, thanks in part to his reputation as a gifted orator who maintained an active speaking tour. He was chosen to formally nominate William Howard Taft — another Ohio native — for re-election at the 1912 Republican National Convention, and he gave the keynote address at the party’s 1916 convention.

Yet, in the years leading up to the 1920 election, it seemed that the Republican nomination would go to Theodore Roosevelt. After serving two terms as president, Roosevelt stepped aside in 1908 for Taft, his handpicked successor. Four years later, he challenged Taft’s re-election bid as a third-party candidate, splitting the Republican vote and paving the way for the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Despite the sheer force of his personality, Roosevelt had aged tremendously in the decade since leaving the White House at age 50. He caught malaria on a post-presidency expedition and his son Quentin’s death during World War I was a blow from which he never recovered.

Roosevelt went to bed on the eve of Jan. 6, 1919, planning to meet in the near future with leaders of the Grand Old Party. He never woke up, as a blood clot in his leg broke off and went into his lung.

Vice president Thomas Marshall said at the time, “Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.”

The 1920 Republican nomination was now wide open, too.

***

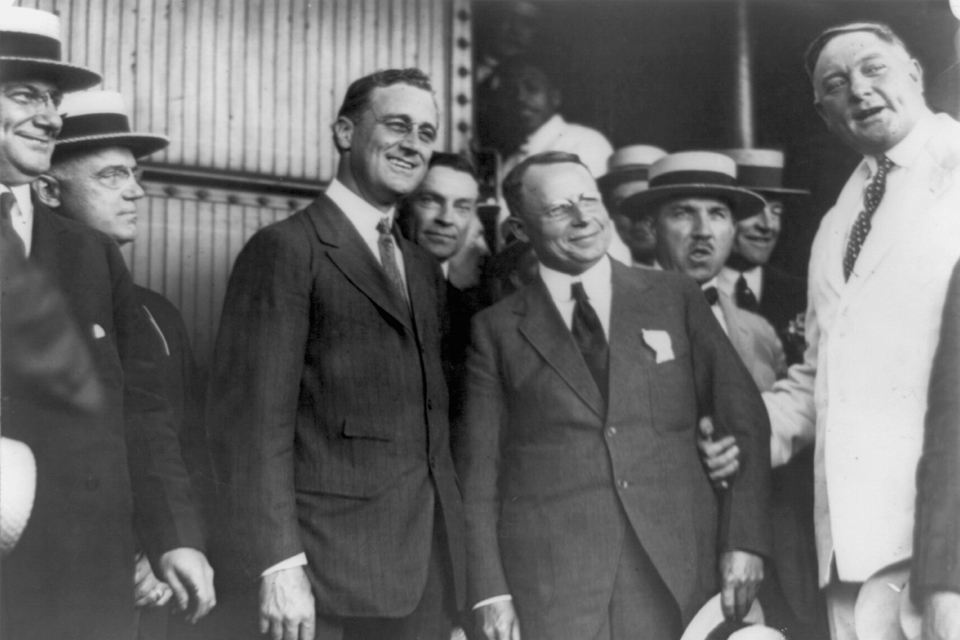

Based on a recommendation, Democratic presidential nominee James M. Cox (above center right) suggested assistant secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt (above center left) be his running mate. A distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, he was young, handsome and regarded as a distinguished speaker (photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

In early June of 1920, Republicans gathered at the Chicago Coliseum on the city’s South Side. Leonard Wood, a Medal of Honor recipient and former Army chief of staff, was regarded as the stand-in for Roosevelt since the two men had fought together in the Spanish-American War. Illinois Gov. Frank Lowden was also a heavy favorite. Harding, who had declared his candidacy the previous December, snared less than 7 percent of the votes on the first ballot, and then a mere 6 percent on the second. But as the deal-making and political horse-trading wore on, Harding became a more popular choice. He took the lead on the ninth round of voting and won his party’s nomination on the 10th.

Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge was selected as his vice-presidential nominee.

Harding’s home in Marion celebrated like it was New Year’s Eve. “Factory whistles were tooted, church bells were rung and Harding’s friends and neighbors gathered on the streets in shouting, laughing groups,” said a newspaper account in the Spartanburg (S.C.) Herald-Journal. The nominee himself, a poker player, seemed surprised, saying, “We drew to a pair of deuces and filled.”

At the end of June, the Democrats met to select their nominee at the Civic Auditorium in San Francisco in what was the first West Coast presidential convention. James Cox skipped the affair to stay in Dayton, but he did send Piqua’s Silver Cornet Band to entertain convention-goers.

The Democratic favorites were William McAdoo, the former secretary of the treasury and Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law, and A. Mitchell Palmer, Wilson’s attorney general. Cox finished third on the first ballot and took the lead on the 12th. He peaked on the 15th ballot before his vote total started to slip.

Finally, on the 42nd round of voting, Cox got a simple majority. Shortly before dawn broke in Dayton on July 6 — nearly eight days after the start of the convention — Cox got word via the Associated Press wire in his office at the Dayton Daily News that he had been selected as the Democratic nominee for president on the 44th ballot. Cox kissed his wife when he found out, then shook hands with the men in the newspaper’s composing room — the only other people in the building at the time.

The reaction in San Francisco was jubilation, doubtlessly bolstered with exhaustion. The Piqua band paraded down Market Street, followed by convention-goers as “the climax of the most colorful national political convention ever held,” wrote San Jose’s The Evening News.

Based on a recommendation, Cox suggested assistant secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt be his running mate. A distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, he was young, handsome and regarded as a distinguished speaker. He was also from New York, which like Ohio was a powerful state when it came to picking presidents.

If there was a concern to be had about the arrangement it was this: The two men had never met.

***

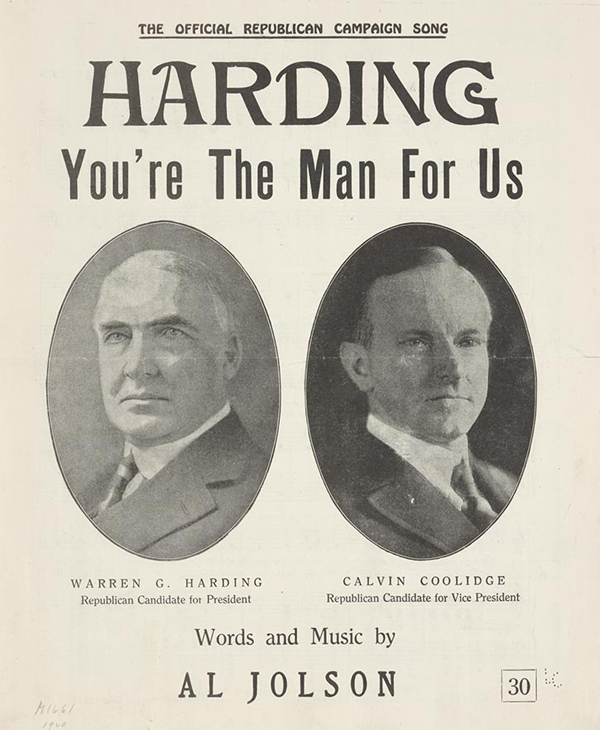

Al Jolson penned the official campaign song for Republican nominee Warren G. Harding and his running mate, Calvin Coolidge. (photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

The low-key approach, in which supporters come to hear a candidate speak at his residence, was a tribute to McKinley. In fact, the flagpole in front of McKinley’s home in Canton was temporarily moved to Harding’s home for the campaign.

It also provided the appearance of calm after the whirlwind changes of the past five years, which included Prohibition, women getting the right to vote, the rise of urbanization and technology, and the aftermath of what was then called The Great War. Harding ran on a “return to normalcy,” appearing dignified and thoughtful on his front porch.

Cox and Roosevelt, on the other hand, crisscrossed the nation campaigning. Roosevelt gave an estimated seven speeches a day, and Cox suggested that he would try to visit all 48 states. He fell short of the goal, visiting 36 — still no small feat in a time when airplanes were a novelty and the transcontinental railroad was barely 50 years old. It was the first modern presidential campaign.

“The Democratic nominees both believe in going direct to the people with their appeals for support,” said U.S. Sen. Pat Harrison, head of the Democratic Party’s speakers bureau. “They have no sympathy with ‘front porch’ campaigns, but will submit their cause and themselves to the public for judgment.”

Democratic organizers believed that Cox’s campaign would force Harding off his front porch. But the campaign came to Marion, with 600,000 people listening to Harding’s speeches in his hometown.

Actors and actresses paid visits on Harding’s behalf, and when the Cleveland Indians and Cincinnati Reds couldn’t come to Marion for a game (it was common in those days for Major League Baseball teams to play exhibition games during the season), the Chicago Cubs played against a local team.

Cox, who had acquired a reputation as a tireless worker while governor, was equally tireless in his campaign. He made a western swing, giving a total of 67 speeches while visiting 22 states. After an appearance at Grays Armory in downtown Cleveland, Fred Charles of the Cleveland Plain Dealer described him as “a steam engine in action.”

Roosevelt was just as energetic and had a similarly taxing travel schedule. “Our candidates are trying not merely to carry the campaign to the country, but to find out what the country is thinking,” Roosevelt said at a stop in Fargo, North Dakota.

Harding had the challenge of corralling the progressive wing of the Republican Party while keeping conservatives happy — something neither Taft in 1912 nor nominee Charles Evans Hughes in 1916 could do. “He got them all on board and that takes some real skill,” says

David Pietrusza, author of 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents. “He made it look easy.”

For his part, Cox had to overcome his endorsement of Woodrow Wilson’s controversial plan for the League of Nations, an international organization formed by the treaty ending World War I, a forerunner to the United Nations. Plus, as the campaign wore on, the Democrats simply ran out of money, according to Pietrusza. The Republicans, who weren’t making extensive travel arrangements, outspent the Democrats by more than 4 to 1, spending more than $4 million.

Harding’s campaign slogan of “a return to normalcy” resonated with voters, who had seen the United States get involved in a World War (and for voters of Irish or German origin, on the wrong side). Weary of war, Americans also faced a recession and the Spanish Flu epidemic, which made more than a quarter of all Americans ill and killed an estimated 675,000 people in the United States during 1918 and 1919.

On Nov. 2, 1920, Harding won the election in a landslide, garnering more than 60 percent of the popular vote and carrying 37 states including Ohio. Cox didn’t even win his home county.

“An irresistible combination of reasons, unreasons and opponents bore him down,” The New York Times said of Cox. “He did all that could be done and more than most men could have done.”

***

As president, Harding faced a daunting task. He had to clean up after World War I, restoring the country’s confidence and righting the economy. He put together the first comprehensive federal budget (before his administration, each department submitted its own budget) and established the Veterans’ Bureau, the forerunner to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

In 1923, Harding embarked on a national tour and fell ill while visiting Seattle. Doctors said it was food poisoning. It was a heart attack, and on Aug. 2, 1923, Harding died.

Two months later, the Senate Public Lands Committee investigated allegations that Albert Fall, Harding’s secretary of the interior, had taken bribes to circumvent the bid process for leasing oil fields in the western United States, including a field in Wyoming called Teapot Dome. Harding might not have known about it, but he was not around to defend himself.

Calvin Coolidge kept Harding’s policies in place and his cabinet intact, but tried to distance himself from his predecessor. “Nobody [wanted] to defend him,” explains Sherry Hall, director of the Harding Home, a museum established in the former president’s Marion residence. “All the things he did took a backseat to Teapot Dome.”

After the 1920 election, people began taking Franklin Roosevelt seriously as a national figure, but his political career and life were nearly derailed a year later, when he contracted polio. The disease ultimately claimed his ability to walk.

Cox made it a point to stay in touch with his former running mate, supporting him and urging him to stay active in politics. The two had become friends on the campaign trail, and in 1924, both attended the Democratic National Convention in New York City. Roosevelt hobbled to the platform at Madison Square Garden to nominate New York Gov. Al Smith.

Four years later, as Smith unsuccessfully ran for president against Herbert Hoover, who had been Harding’s secretary of commerce, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York. Four years after that, Roosevelt ran for president, defeating Hoover. “The contacts he made in 1920 got him elected president,” Pietrusza says.

Of the four men on the major-party tickets in 1920, James Cox was the only one not to be elected president (Coolidge won in 1924). In fact, he never ran for office again. He went back to his publishing business, buying newspapers in Atlanta and Miami, and laying the groundwork for his media empire. Today, Cox Media is a billion-dollar company, owning 24 newspapers, including the Dayton Daily News (the first one Cox ever bought), 14 television stations and 57 radio stations.

“He was a newspaperman at heart,” says historian and researcher Mary Kay Mabe. “His newspaper was his mechanism to do right. Politics fit in, but the newspaper was really his baby.”

Related Articles

Visit This Gothic-Style Temple in Lake County

The northeast Ohio community of Kirtland played a pivotal role in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. READ MORE >>

How the Wright Brothers’ Sister Shaped History

Katharine Wright was her famous brothers’ not-so-silent partner, aiding her siblings Orville and Wilbur in their quest to get their dreams of mechanical flight off the ground. READ MORE >>

This Ohio Barn Theater Preserves a Long-Running Tradition

One of a handful of historic Ohio venues of its kind, Rabbit Run Theater in Madison has been hosting summer stage shows since 1946. READ MORE >>