Ohio Life

My Ohio: Blooming Generosity

For one writer, lilacs have a special quality beyond their beauty and fragrance.

Related Articles

Old Slate Farm, Mount Vernon

Katie and Brad Carothers grow beautiful flowers that they turn into romantic floral designs for weddings and other events. READ MORE >>

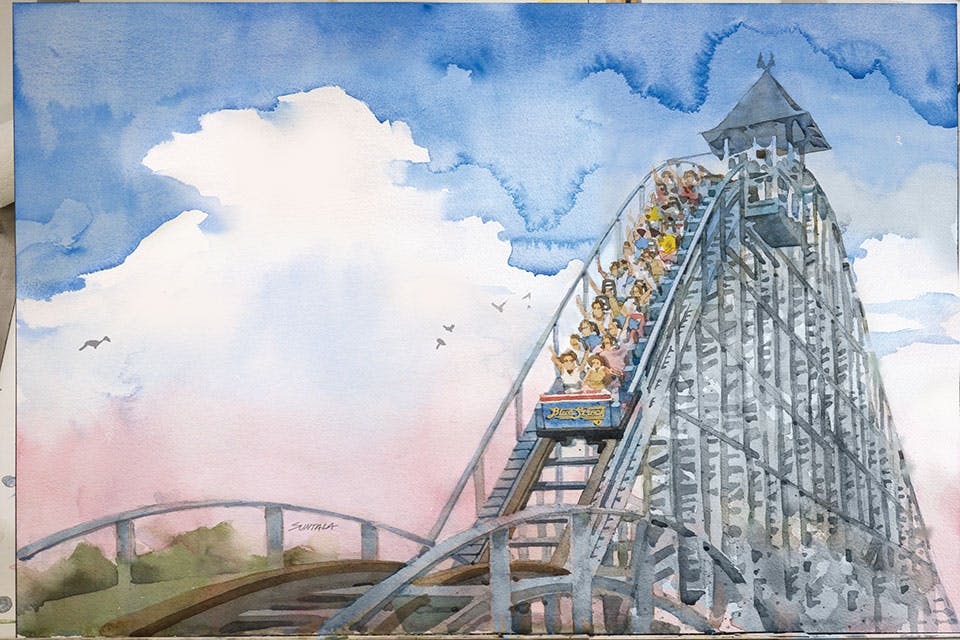

Why We Love Cedar Point

H. John Hildebrandt worked at Cedar Point for 40 years. As the amusement park marked its 150 anniversary, he looked back at his and our connection to Ohio’s summer playground. READ MORE >>

Toledo: Birds, Boats & Blooms

From exploring the Great Lakes to spotting birds at Woodlawn Cemetery & Arboretum, Toledo offers a variety of ways to connect with nature. READ MORE >>