Arts

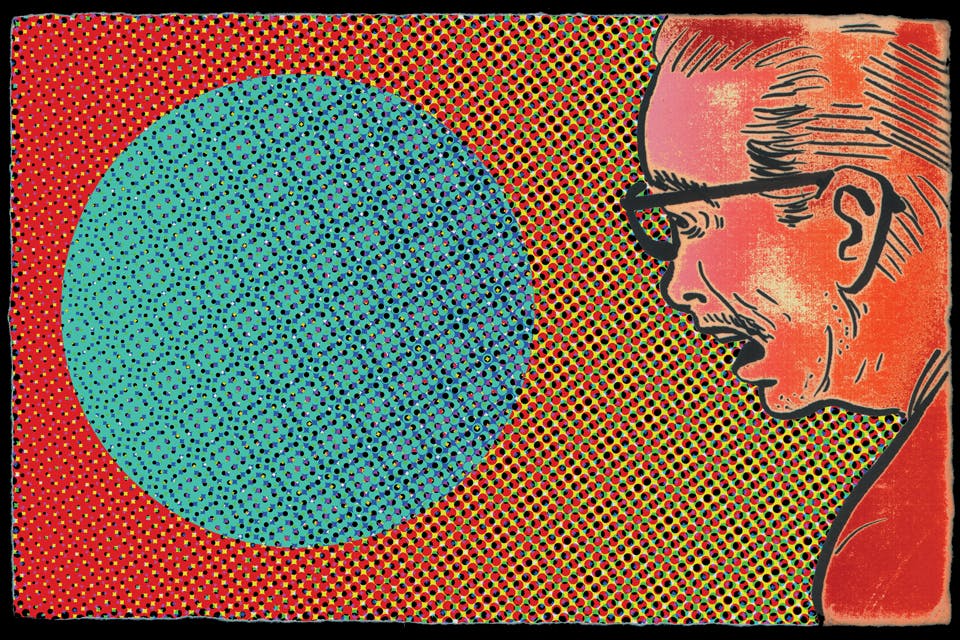

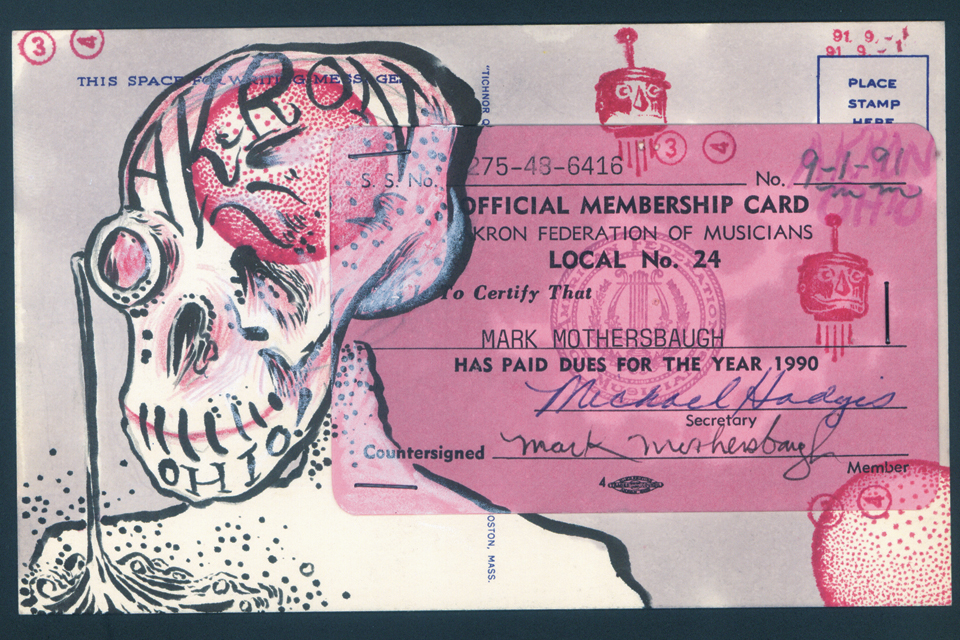

A Clear Vision

Exhibition looks Ohio native and Devo frontman Mark Mothersbaugh's inventive visual art.

Related Articles

See ‘Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike’ in Cincinnati

Explore the evolution of bicycle design at the Cincinnati Art Museum during “Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike,” on display from April 4 through Aug. 24. READ MORE >>

Celebrate Legendary Women at These 5 Ohio Museums

Visit these sites that honor individuals who left an indelible mark on history, from a pioneering suffragist to a famous sharpshooter to a literary icon. READ MORE >>

Engage Your Kids’ Sense of Wonder at 5 Ohio Science Centers

Curiosity fuels learning at these kid-focused destinations across our state that are filled with hands-on experiences, insightful exhibits and big fun. READ MORE >>