Arts

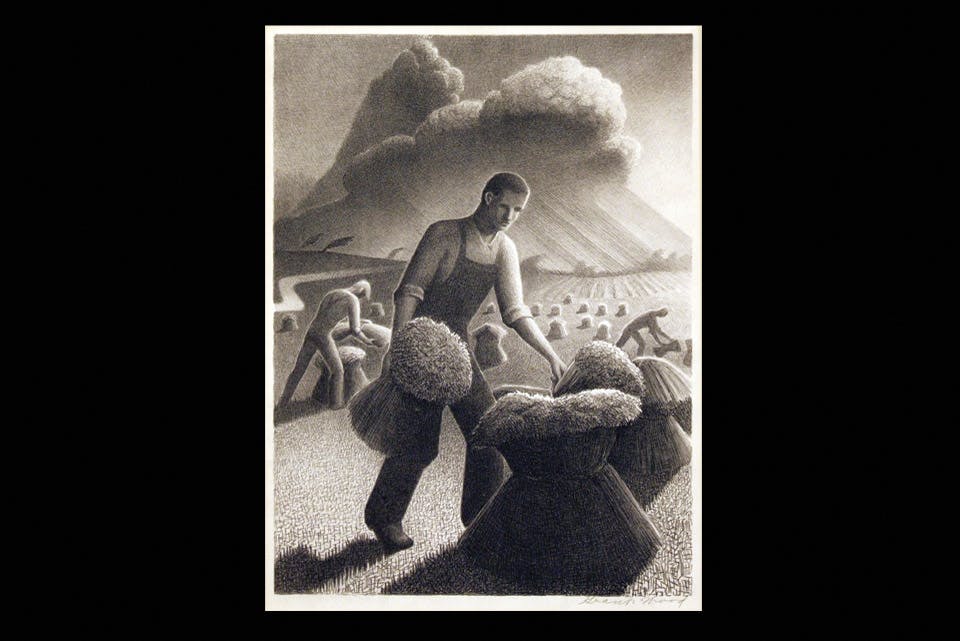

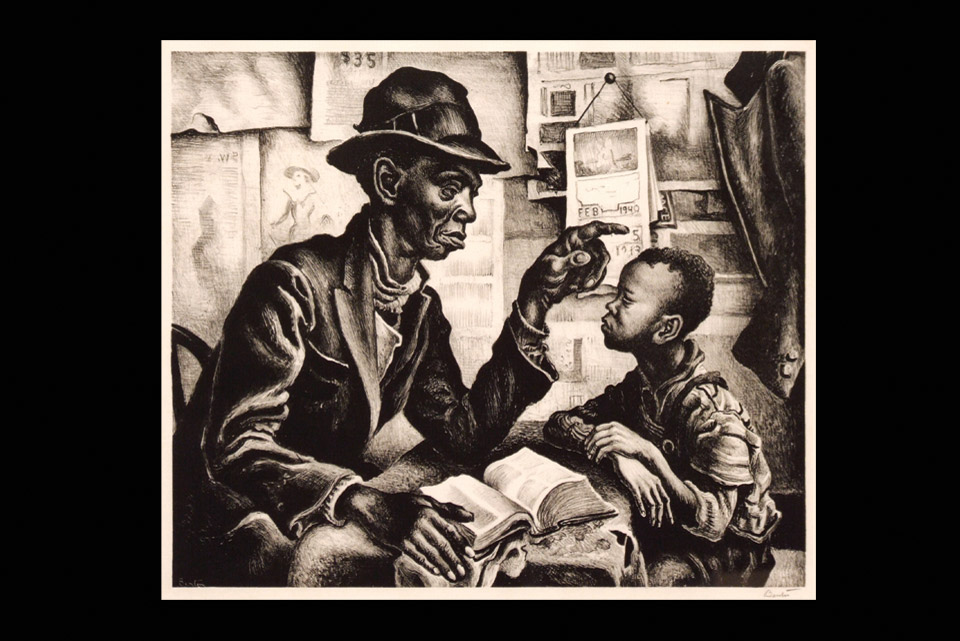

Art for All

At the height of the Great Depression, artists banded together to offer hope through their work.

Related Articles

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>

See ‘Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects’ in Lancaster

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio hosts an artifact-focused exhibition that tells the story of our state through a collection of family keepsakes and iconic inventions. READ MORE >>

Historic Marker Installed at Home of Orville Wright

Hawthorn Hill, the Oakwood home where aviation pioneer Orville Wright lived with his sister and father, now bears a new marker celebrating its place in American history. READ MORE >>