The Cleveland Orchestra: A Century of Symphonies

As the Cleveland Orchestra celebrates its 100th season in 2017, we looked back at those who lifted it to worldwide acclaim.

October 2017

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Roger Mastroianni

October 2017

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Roger Mastroianni

While his friends listened to the latest Beatles and Rolling Stones albums, Donald Rosenberg played recordings of Beethoven symphonies and watched CBS telecasts of “Young People’s Concerts” conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

“I guess I was the consummate nerd,” Rosenberg, 65, says with a laugh, recalling his youth in Westwood, New Jersey. “But classical music has always gripped me emotionally and taken me to another world — a world where, in many cases, words are unnecessary.”

The Shaker Heights resident spent 28 years reviewing Cleveland Orchestra concerts for the Akron Beacon Journal and The Plain Dealer. In 2000, he authored The Cleveland Orchestra Story: “Second to None,” a 700-page history charting the rise of the ensemble, which began its centennial season at Cleveland’s Severance Hall Sept. 23 with “The Cunning Little Vixen,” an opera written by Czech composer Leoš Janáček in 1923, performed with accompanying digital animation.

“The title of my book comes from a phrase coined by [former Cleveland Orchestra music director] George Szell when he was asked about the quality of the orchestra,” Rosenberg says. “He didn’t want to say it was the best orchestra in the world, but in a way he did say that.”

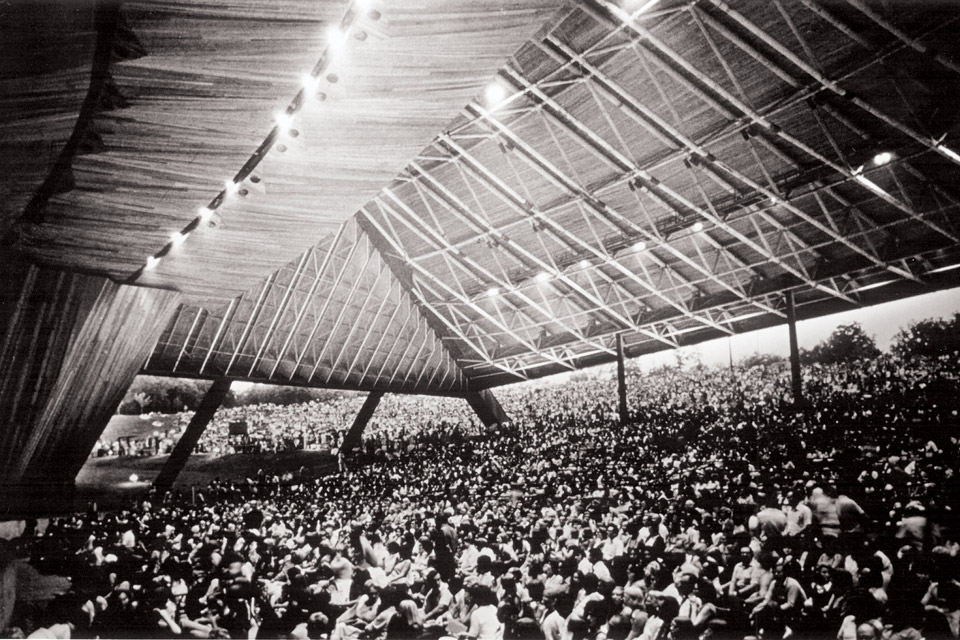

Szell’s sentiment is shared the world over. Since it made its debut on Dec. 11, 1918, the orchestra has performed around the globe. Orchestra recordings have won eight Grammy Awards out of 29 nominations, and each year, more than 300,000 patrons attend concerts in northeast Ohio, including at Severance Hall, the classical/art deco gem that opened in 1931; or at Blossom Music Center, an amphitheater that has been the orchestra’s summer home since 1968.

“The Cleveland Orchestra is one of the finest in the world,” says Rosenberg, now the editor of EMAg, the magazine of Early Music America, the service organization for the field of historical performance in North America. “It has clarity, precision, balance and a refusal to overstate. The Cleveland Orchestra is a very subtle ensemble that is able to emphasize the best qualities of the music it is performing.”

***

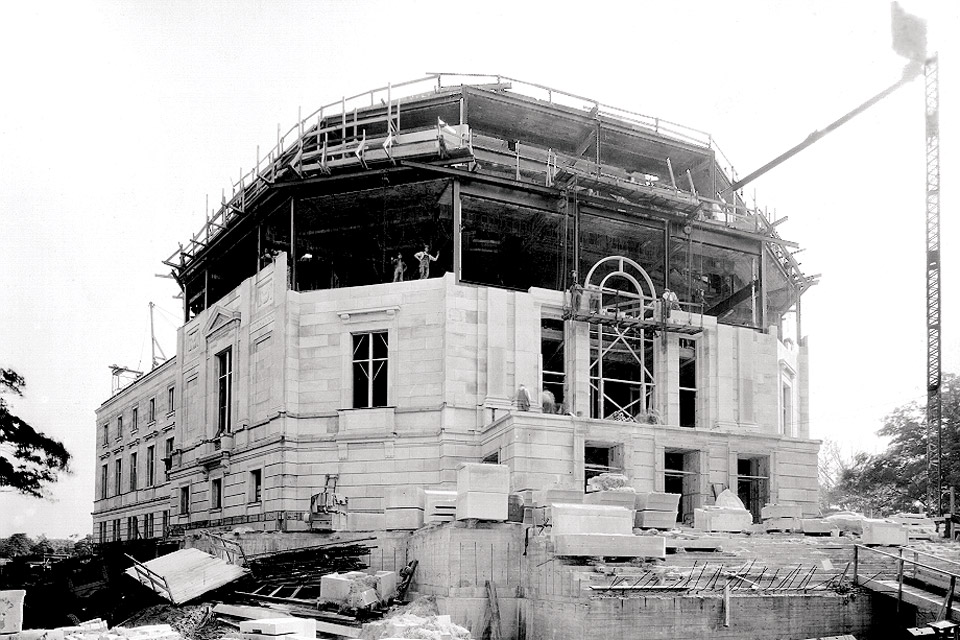

Construction of Severance Hall on Cleveland’s University Circle was completed in 1931. (photo courtesy of Walker and Weeks)

Although the Cleveland Orchestra’s music directors have all been men, a woman led the charge to found it. Beginning in 1901, Cleveland socialite, pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes organized concerts that included performances by orchestras from Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and New York.

“Adella was a very strong-willed woman and very smart,” Rosenberg says. “The ensembles she brought to town served as an overture to creating a permanent orchestra in Cleveland. Adella came from the upper echelon of society and was able to explain to the bigwigs in town what having a permanent orchestra would do for the city.”

Each of the seven music directors who’ve taken up the baton since the orchestra’s founding has added a chapter to the ensemble’s legacy. They include first director Nikolai Sokoloff, who conducted the orchestra’s first studio recording in 1924 (an eight-minute rendition of Tchaikovsky’s “1812” overture, which filled both sides of a 78 rpm record); the colorful Artur Rodziński, who kept a loaded revolver in his back pocket during concerts as a good luck charm; and George Szell, the consummate perfectionist, credited with shaping the crisp Cleveland Orchestra sound that remains today.

***

Emilio Llinás, the Cleveland Orchestra’s assistant principal second violin, is celebrating his 50th year with the ensemble. He recalls his heart racing when, as a 28-year-old, he prepared to audition for George Szell in 1968.

“Auditions back then were a truly nerve-wracking experience,” Llinás says. “Today, applicants know in advance what they’re expected to play. But when I auditioned, you played several violin concertos of your choice, and then all kinds of music was put in front of you, which you were expected to sight read. The audition lasted about 20 minutes. I was on stage by myself, there was no accompanist, and Szell, along with three or four musicians, was sitting in the last row of Severance Hall in the dark watching me.”

After the violinist finished, Szell approached the stage, examined Llinás’ instrument — a rare piece crafted by 18th-century Spanish violin-maker Jose Contreras — and walked off without saying a word about the tryout. The personnel manager offered some much-needed encouragement: “Don’t leave,” he whispered. “I think it’s in the bag,” echoing the expression Llinás later learned Szell used after a successful recording session.

The violinist agrees that the music director’s reputation of having an obsession with flawlessness is not an exaggeration, right down to his exacting suggestions about the correct way to mop the Severance Hall floor.

“He was a control freak, but not in a bad sense,” Llinás explains. “Szell was one of the greatest masters who ever lived. He knew scores by heart like very few conductors do these days and wanted to make sure his musicians were hard workers who were constantly striving to improve themselves. He would watch you for the first two or three weeks after you joined the orchestra. After that, if he respected you, you had no problem. But if he thought you were trying to get away with something, that was trouble.”

***

Blossom Music Center has been the Cleveland Orchestra’s summer home since 1968. (photo courtesy of Westlake, Reed, Leskosky)

Just as George Gershwin’s racially charged “Porgy and Bess” broke new ground when it debuted 82 years ago, so, too, did the Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus’ 1975 interpretation of the masterpiece: Not only was it the first time the complete opera was recorded in stereo, but the three-LP compilation also had the distinction of being the first opera recording ever made by the Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus.

To Joela Jones, a then-recent graduate of the Cleveland Institute of Music who’d been appointed the orchestra’s principal keyboardist four years before, playing such an instrumental part in the recording is a high point in her career.

“Maybe its because I’m an American,” she says, “but I’m very proud that this magnificent piece was written by an American and performed so beautifully by an American orchestra and conducted by Lorin Maazel, an American conductor.”

Unlike his predecessors, who focused on European symphonies, says Jones, Maazel was a versatile conductor who also embraced the operatic.

“Maazel approached ‘Porgy and Bess’ the way he would a work by Wagner or Puccini,” she explains. “He gave it tremendous vitality and value, elevating it to where it should be. I think that comes across in our playing.”

Maazel and the recording’s producer, Michael Woolcock, left no detail to chance. And that included the honky-tonk piano sound the duo decided would be a key component of the overture, which Jones would play.

Maazel and Woolcock prowled the hallways and back rooms of Cleveland’s Masonic Hall — where the recording would be made — in search of a badly out-of-tune piano that would provide the sound they needed. They found one and had it moved to the stage, next to the 9-foot concert grand, which Jones would also play.

As was the practice before recording sessions commenced, a piano tuner was called in to check the concert grand. He arrived early when no one was around, finished the job and left.

“When Maazel came in several hours later,” Jones recalls, “he just about died.”

The piano tuner had done his work well — on both pianos. The honky-tonk sound Maazel and Woolcock fortuitously discovered for the overture was gone.

“So they paid him,” Jones recalls, “to untune it.”

***

Robert Vernon retired in 2016 after spending 40 years with the Cleveland Orchestra as principal viola. Vernon’s admiration for music director Christoph von Dohnányi is readily apparent as he recalls the ensemble’s recording session for Mozart’s Symphonie Concertante in E-flat major, K. 364.

“Dohnányi was music director during the ’90s, a time when the orchestra was going through a kind of second golden era, a time when we were the most recorded American orchestra,” Vernon says. “It was an incredible experience because we were playing our usual subscription concerts during the week and then heading to the studio on weekends.”

Vernon, who describes the Mozart work as “the backbone of wonderful pieces for violin and viola,” was understandably anxious: He was playing the viola solo and wanted it to be perfect. But he was worried there would not be enough time to make tweaks before the recording session ended.

“I remember telling Dohnányi that we only had time for one run through, and I thought that was a little unfair, that we needed a little more time to at least be able to make some corrections to the part.”

Dohnányi understood and arranged with executives at the Decca record label to build in time for extra takes.

“He didn’t need to do that,” the violist says. “Clearly, he was a kind man who had the musicians’ best interests at heart.”

***

Franz Welser-Most is marking his 16th year as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. (photo by Roger Mastroianni)

The Cleveland Orchestra’s 100th season is only one of many milestones achieved over the last century. But the ensemble has no intention of resting now. While many arts organizations fret over attracting younger audiences, Ross Binnie, chief brand officer and director of the Cleveland Orchesta’s Center for Future Audiences, is delighted by the fact that 20 percent of its classical concert attendees — some 40,000 patrons annually — are under age 25.

“Over the years, assumptions have been made that classical music is a dying art form,” Binnie says. “But we believe the music itself has no barriers and is timeless. So we’ve taken steps to engage new audiences and make our performances more accessible.”

Created in 2010 to fund programs geared to engage new generations of classical-music lovers, the Center for Future Audiences supports a variety of programs, including free admission to select performances for audience members under 18.

“There isn’t a stronger partnership between a music director and an orchestra in this country,” he says. “Franz [Welser-Möst, who is marking his 16th season as music director] has really tapped into our community. He leads preshow discussions that explore all facets of the orchestra and will conduct 2018’s Star Spangled Spectacular free concert in downtown Cleveland on Mall B.

“I feel the future of this music is brighter than ever,” Binnie adds. “We’re experiencing the enthusiasm of all ages, which is terrifically important. Our musicians comment that they feel the energy and play better as a result. It’s really refreshing to say that the Cleveland Orchestra is ‘cool’ once again.” For more information about the performances scheduled for the Cleveland Orchestra’s centennial season, visit clevelandorchestra.com.

Related Articles

8 Tribute Bands Rocking Ohio Stages This Season

Venues across Ohio are turning up the nostalgia with tribute acts that channel the sound and spirit of legends ranging from the Eagles to Pink Floyd. READ MORE >>

6 Symphonic Shows in Ohio This Fall

From symphonic blues in Toledo to a soulful tribute in Dayton, classical musicians across Ohio are tuning up for a season of performances. READ MORE >>

Fall Arts Preview: 12 Exhibitions, Shows and Festivals to See This Season

Save the date for these arts favorites happening across Ohio between now and the end of autumn. READ MORE >>