Arts

Character Study

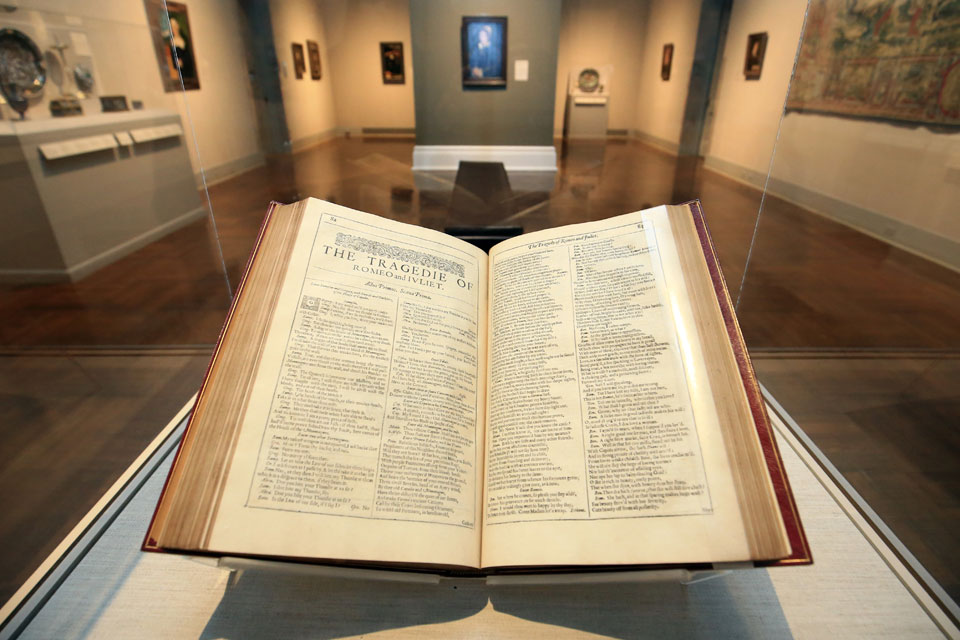

The Toledo Museum of Art celebrates the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death with an imaginative take on the Bard’s body of work.

Related Articles

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>

See ‘Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects’ in Lancaster

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio hosts an artifact-focused exhibition that tells the story of our state through a collection of family keepsakes and iconic inventions. READ MORE >>

See ‘The Triumph of Nature: Art Nouveau from the Chrysler Museum’ at the Dayton Art Institute

This exhibition, which runs through Jan. 11, showcases more than 120 works that explore our connection with nature. READ MORE >>