Author Mary Doria Russell Finds the Truth at the O.K. Corral

We talk with author Mary Doria Russell about the famous gunfight we only think we know.

September 2016 Issue

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Emily Nichols

September 2016 Issue

BY Linda Feagler | Photo by Emily Nichols

It was over in 30 seconds. But by the time the smoke cleared from the gunfight at the O.K. Corral — which happened in Tombstone, Arizona, on Oct. 26, 1881 — three civilians lay dead and lawmen Wyatt Earp and John “Doc” Holliday were on their way to achieving larger-than-life stature in the annals of Wild West history.

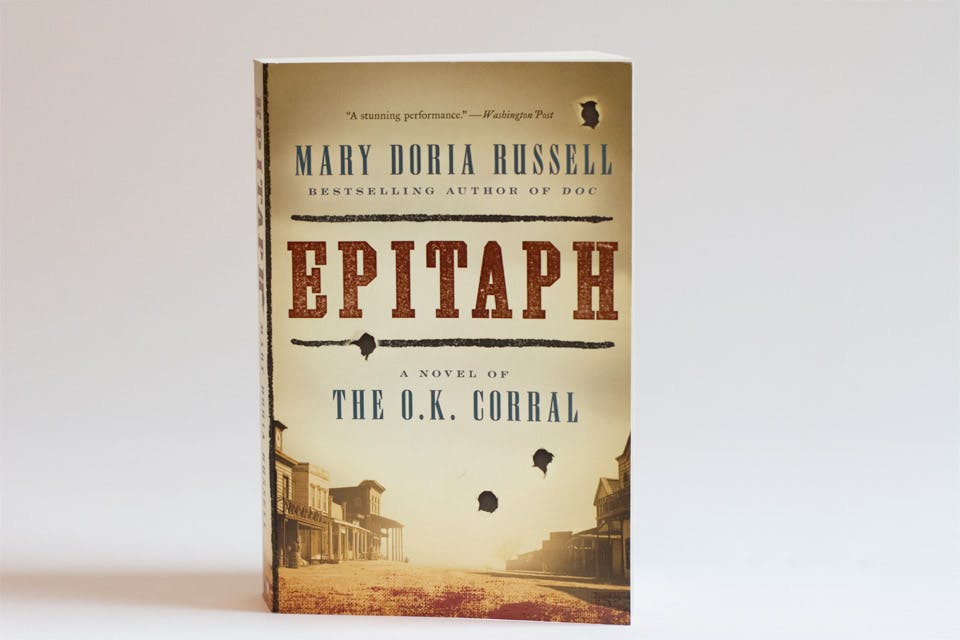

In her latest book, Epitaph: A Novel of the O.K. Corral, Lyndhurst author Mary Doria Russell revisits the iconic skirmish and explores the dramatic betrayals, jealousies and coincidences that led to the most famous shoot-out in 19th-century America.

“Although it happened 135 years ago, the gunfight is tragically topical since then, as now, opinions were divided along political lines,” Russell says. “One side believed Wyatt Earp and his brothers were badge-wearing thugs and murderers who killed innocent people because of a personal feud, and that ‘Doc’ Holliday was worse than any of them. … The other side contended that the Earps were valiant lawmen defending their city from violent criminals and saw Holliday as a loyal friend who was a gentleman and a scholar.”

Russell, 66, who will receive an Ohioana Book Award for Epitaph this month from the Ohioana Library Association, talked to us about why the Old West is a source of fascination, who her allegiances lie with and what lessons continue to resonate.

Why does the story of this particular gunfight still capture our imagination?

I think it’s because it’s a gripping example of a revenge drama, a genre that goes back to the Greeks and probably further. In the first act, a crime is perpetrated. In the second act, the perpetrators appear to be getting away with it. And in the third act, the hero exacts bloody revenge because the justice system has not delivered what it promised.

Sadly, that’s what you see today on the streets of America. The gunfight was basically an officer-involved shooting with both armed and unarmed men. Afterward, there was a monthlong legal hearing that cleared the officers. In retaliation, friends and relatives of the dead men attacked the Earp brothers directly, crippling Virgil and killing Morgan. Wyatt responded with a series of brutal extrajudicial executions, but he was not beyond the law. He was wanted for murder in Arizona and had to leave the territory after that.

My father was a cop and he taught me early on that if people stop believing the justice system works, the next step is vendetta. And that, I’m afraid, is what we are setting ourselves up for now.

So much has been written about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Why did you choose it to be the subject of your latest book?

Any book has a number of reasons why you might write it. I grew up watching cowboy television shows and was a horse-crazy girl who saved my baby-sitting money to spend on riding lessons. But my interest in the frontier was sparked again when I served on the planning and zoning commission for the city of South Euclid. It was my responsibility to research ordinances about gun shops and topless bars. Although I had seen the movie “Tombstone” many times, I watched it with new eyes as I realized I was dealing with the same issues that frontier boomtowns did.

I decided to write Doc [which was published in 2011] after reading the biography Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait written by his [cousin] Karen Holliday Tanner. When I went on tour for that book, people would ask why I hadn’t written about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. The answer was because I thought everybody already knew everything there was to know about it. But then a woman came up and introduced herself as the great-grandniece of Tom McLaury, one of the men who was killed in the gunfight. She said, “I just want you to know that Tom and his brother Frank did not go to Tombstone that day to make trouble. They were there to catch a train to go to my great-grandmother’s wedding.”

Now that put a different spin on things for me. It was the moment I knew I might have a new way into the story. It led me to not take at face value any of the characterizations of the people who were called the outlaws, and I began to see things from multiple points of view.

Your debut novel, The Sparrow, was published in 1996, when you were 46, and it was rejected 31 times by 31 agents. What led to your perseverance to keep writing?

I had just enough encouragement from people who were not married to me or married to someone who was my relative, as well as from people in the [publishing] business to let me believe I wasn’t deluded about the manuscript. If anyone else would have told me their story had been rejected so many times I would have said,

“There’s a message you’re not getting here. You might want to consider a different way to spend your time.”

And I think for most people that is good advice. But I also think many writers believe that having completed a novel is the same as having finished it — when in fact, you’ve just got a first draft. Being a writer means playing a multifaceted game. I can go very quickly from being my own best editor to my own best critic. I know when it’s bad, and I don’t just slough it off. I will edit every single chapter over and over and over again.

I had the opportunity to speak with concert pianist Valentina Lisitsa, and I asked her how many times she practiced a piece before she performed it in concert. She thought a moment, and said she estimated she practiced it 8,000 times, learning the movements and nuances section by section, smoothing out the rough spots and making it better and better. That’s what I try to do with my novels. I don’t take shortcuts. That’s why it takes me three or four years to write one.

Epitaph paints a rich tapestry about life in the Old West? How did you research the period?

There are a lot of good biographies and histories available now. I also spent five days on horseback in the mountains surrounding Tombstone to take the same vendetta route Wyatt Earp did to hunt down the men who killed his brother.

The journey was all off-road, riding up and down gullies in mountains that were like giant piles of rubble. If you come off your horse, you’ll hit cactus and rock. It is definitely not for amateurs. I trained for the trip for six months — and I hate exercise! But I kept going back to what Mark Twain said, “A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way.” As I result, I came to understand what spending eight to 10 hours in the saddle was like for a man like “Doc” Holliday, who was very sick and not saddle-hardened as Wyatt and the others were.

In a program you presented, you mentioned that if you know something is true, you never try to contradict it. Does that prove to be challenging when you are writing?

Even my two science fiction novels, The Sparrow and Children of God, have a historical context. I always try to make the story as realistic as I can. Sometimes I really want things to go another way, but I just can’t make that happen. There have been many times when I’ve said, “Oh God, if only … ” I really wanted “Doc” to have a better life. I wanted him to beat tuberculosis and go home to marry and have children and have the life he was born for. But he died at 36, and there was nothing I could do about that. So all I could do was give him the compassion and respect I believe he deserved.

What surprised you most when you were researching this book?

Well, I’d have to start with the fact that the gunfight at the O.K. Corral had nothing to do with cows! It’s always framed as lawmen versus cattle thieves, but it was really about gun-control ordinances in Tombstone. And the gunfight did not take place in a corral. Early on, it became much easier to say that than call it “the officer-involved shooting in the alley behind Fry’s Photography Studio near the corner of First and Fremont, a little north of the O.K. Corral.”

And then there’s the theme song for the 1950s TV show, “The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp,” which included the lyrics, “The West, it was lawless, but one man was flawless and his is the story you’ll hear.” The fact is Wyatt was far from flawless. It was Josie Marcus, who technically never married Earp but was with him for 49 years, who made sure his name was clear and shaped the image we have of him.

Is there one person you’ve written about in Epitaph who is your favorite or whom you identify with the most?

I am very maternal about “Doc.” My heart goes out to him because he was so lonely and misunderstood. He was headed for a life in Atlanta as a dentist until he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at age 22 — the same disease he watched his mother die of when he was 14.

Holliday headed west because the popular theory of the time was that sunshine and dry air would be good for the lungs. So here was a man who was highly educated, who read Homer in Greek and Virgil in Latin and Flaubert in French, who finds himself on what must have seemed to be the far side of the moon.

Nobody’s got money for dentistry here, so what can he do? Nearly every job available either takes strength or stamina, and he’s got neither. So he gambles. He’s not proud of it, so he keeps it a secret from his family for years because it was considered to be the male equivalent of being a prostitute. To the very end of his life, he was searching for something that would save him. His story is heartbreaking.

The 2016 Ohioana Book Awards take place at the Ohio Statehouse. Reservations are required. For more information, visit ohioana.org.

Related Articles

Enjoy Books and Brews at these 3 Ohio Shops

Visit these three Ohio bookstores that go beyond the printed page to offer coffee, beer, wine and more. READ MORE >>

Follow-Up With ’True Raiders‘ Author Brad Ricca

The Cleveland-based author’s new book delves into the details behind a real-life 1909 expedition to find the Ark of the Covenant. READ MORE >>

Ohio Literary Trail

This book lover’s road trip includes the family home of the woman who helped change Americans’ views on slavery and a museum celebrating the art of the picture book. READ MORE >>