Arts

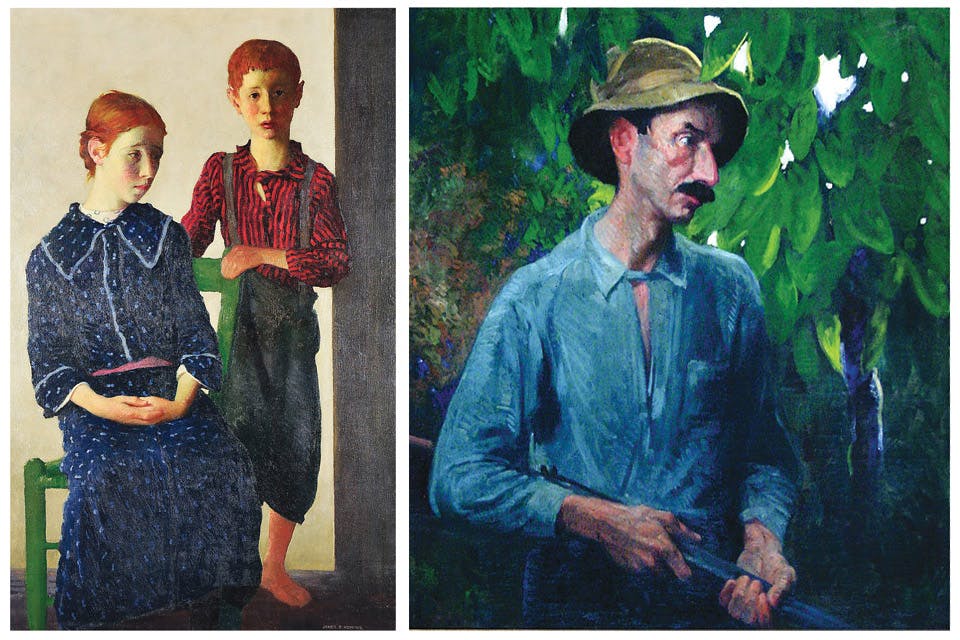

Faces of the Heartland

The Columbus Museum of Art highlights Ohioan James R. Hopkins’ innovative early 20th-century paintings depicting the Cumberland mountaineers of Kentucky.

Related Articles

4 Outdoor Adventures in Appalachian Ohio

From camping that the entire family can enjoy to a hike featuring one of the best views in the state, Ohio’s Appalachia region lets you choose your own adventure. READ MORE >>

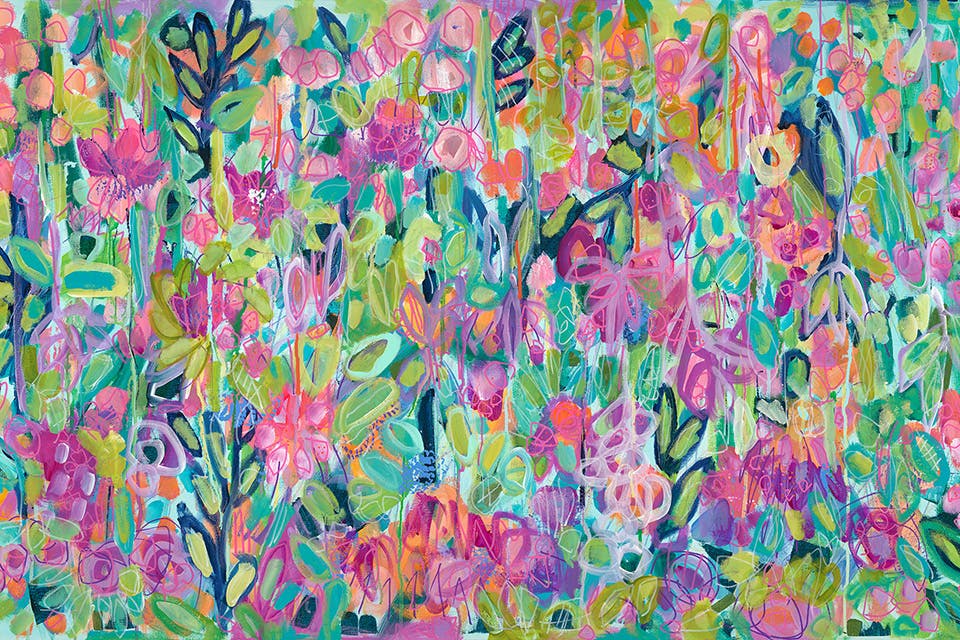

Flowers Power Alisa H. Workman’s Beautiful Paintings

The southwest Ohio-based artist embraces spontaneity in creating her floral-inspired canvases. READ MORE >>

View a Whimsical Cloth Circus at Canton Museum of Art’s ‘Without a Net’

California-based artist Susan Else’s vibrant and fun creations are the focus of this exhibition, which runs from Nov. 21 through March 3. READ MORE >>