Arts

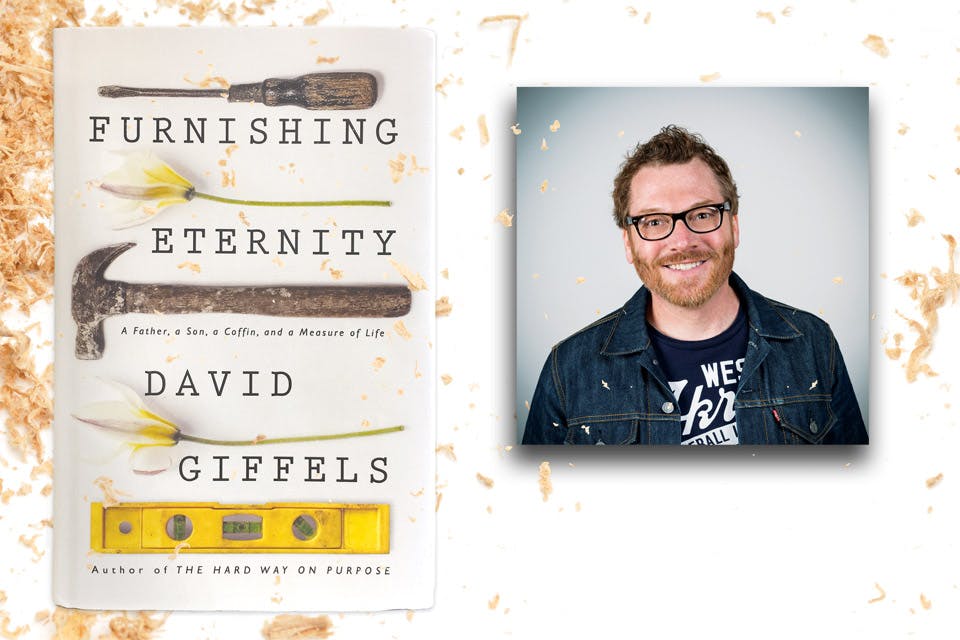

Life According To … Author David Giffels

The Akron author takes on the most unusual of projects: building the coffin in which he will one day be buried. In 2017, Giffels talked with us to share what he learned along the way.

Related Articles

Enjoy Books and Brews at these 3 Ohio Shops

Visit these three Ohio bookstores that go beyond the printed page to offer coffee, beer, wine and more. READ MORE >>

Follow-Up With ’True Raiders‘ Author Brad Ricca

The Cleveland-based author’s new book delves into the details behind a real-life 1909 expedition to find the Ark of the Covenant. READ MORE >>

Ohio Literary Trail

This book lover’s road trip includes the family home of the woman who helped change Americans’ views on slavery and a museum celebrating the art of the picture book. READ MORE >>