Arts

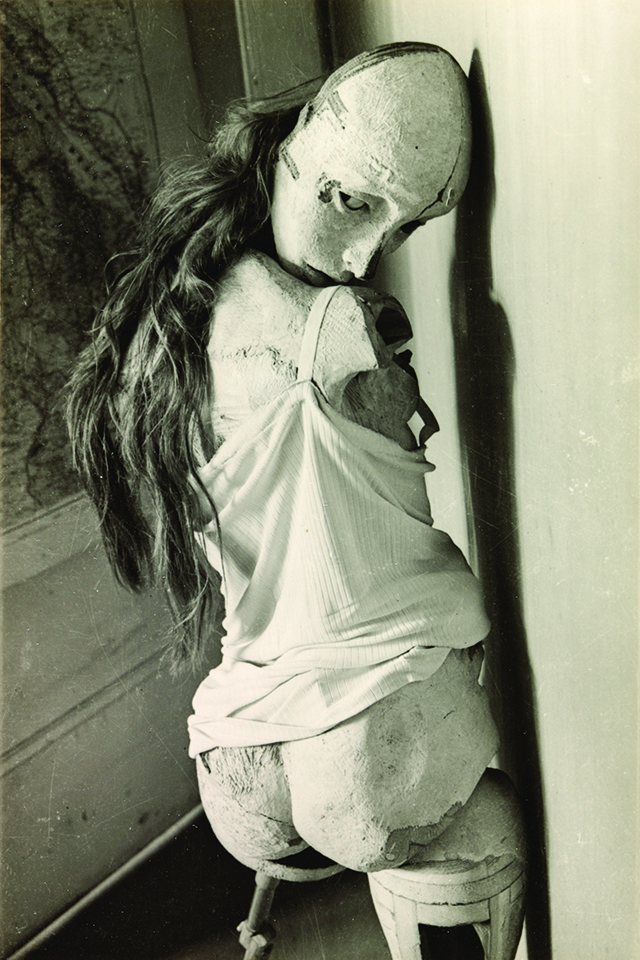

Mind Games

The Cleveland Museum of Art hosts a photography exhibition that explores the secrets of the psyche.

Related Articles

Concert Posters, Natural History and the Art of Derek Hess

This Cleveland Museum of Natural History exhibition shows how the artist’s concert-poster past evolved into fine art shaped by paleontology, animals and ingenuity. READ MORE >>

Every Exhibition at the Dayton Art Institute in 2026

From traveling shows featuring the works of artist Tony Foster and William H. Johnson to focus exhibitions curated from the museum’s collection, here is what’s on the schedule this year. READ MORE >>

New Immersive Augmented Reality Experience Coming to COSI

Starting Jan. 30, visitors to the Columbus science destination can explore and interact with imaginary, virtual worlds through this holographic theater exhibit. READ MORE >>