Arts

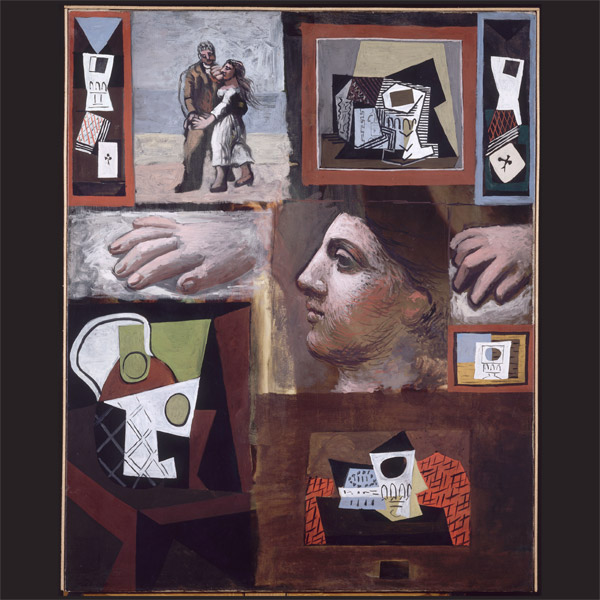

Picasso’s Evolution

The Columbus Museum of Art examines how World War I led Pablo Picasso to go beyond cubism.

Related Articles

See ’Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects’ in Lancaster

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio hosts an artifact-focused exhibition that tells the story of our state through a collection of family keepsakes and iconic inventions. READ MORE >>

See ‘The Triumph of Nature: Art Nouveau from the Chrysler Museum’ at the Dayton Art Institute

This exhibition, which runs through Jan. 11, showcases more than 120 works that explore our connection with nature. READ MORE >>

See ‘Radiance and Reverie: Jewels from the Collection of Neil Lane’ in Toledo

This exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art traces a century of jewelry creation by legendary designers. It is on view from Oct. 18 through Jan. 18, 2026. READ MORE >>