Arts

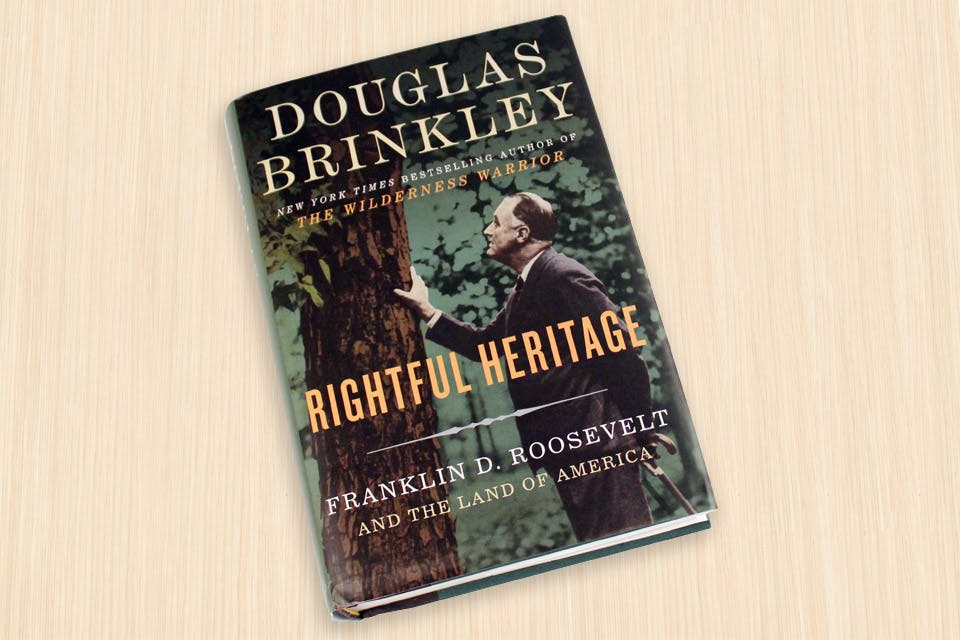

Author Douglas Brinkley on Writing and Preserving History

The former Perrysburg resident talks FDR, conservation and his love for history.

Related Articles

Learn the Sweet History of The Dawes Arboretum at Maple Syrup Day

The Newark arboretum’s founders, Beman and Bertie Dawes, began harvesting sap for maple sugar in 1919. Today, the annual Maple Syrup Day shares that heritage with visitors. READ MORE >>

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>

See ‘Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects’ in Lancaster

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio hosts an artifact-focused exhibition that tells the story of our state through a collection of family keepsakes and iconic inventions. READ MORE >>