The Life and Art of Don Drumm

The Akron-based artist works in materials that are more commonly associated with the factory floor than the art gallery.

April 2015 Issue

BY Jim Vickers | Current Photo by Jerry Mann, Historic Photo Courtesy of Don Drumm

April 2015 Issue

BY Jim Vickers | Current Photo by Jerry Mann, Historic Photo Courtesy of Don Drumm

Don Drumm’s art spans the whimsical and the natural, the recognizable and the abstract. His range is particularly evident in the long list of large-scale works the sculptor and designer craftsman has created during the past six decades — what he affectionately refers to as his “museum pieces.”

But rather than being confined to a white-walled gallery, his most well-known creations are boldly displayed in public places. You may already be familiar with some of them and not realize it. Anyone who has attended Bowling Green State University since the late 1960s has seen Drumm’s 10-story wall relief on the exterior of the Jerome Library, and his 15-foot-tall, steel structure at Kent State University bears a hole from where a bullet pierced it on May 4, 1970.

In Akron, Drumm’s works are part of the fabric of the city, from the relief of elephants and giraffes at the Akron Zoo to the brushed aluminum sun and moon watching over the Akron Public Library lobby to the Garden of Fantasy sculpture that seems to levitate inside the Jean and Milton Cooper Cancer Center.

He has become synonymous with using materials and methods most commonly associated with industry to forge his pieces, infusing them with a lightness that contrasts the nature of their inception, be they cast in aluminum, cut from steel or sandblasted into cement. At times, his works depict animals or organic shapes. Others are abstract, nonobjective forms, which Drumm counts among his favorites.

“They’re to be appreciated for their design, the negative space, the color of the material … their craftsmanship and just interesting things within space,” he says of the latter. “But I do a lot of realistic stuff. I like birds. I like leaves.”

Drumm will celebrate his 80th birthday this month, and anyone who spends time with the man realizes that his drive to create burns strong. He still does commissions while also designing functional and decorative pieces for the home that are sold at the Akron gallery he and his wife, Lisa, opened in 1971, as well as others throughout the U.S.

“His stuff is always changing, and it’s always evolving,” says Daniel Dahl, the executive director of E.J. Thomas Hall, a performing arts center at the University of Akron. “But it’s also so iconic. You see his style and you know that’s Don.”

Wise suns with all-knowing faces cast in aluminum have arguably become Drumm’s most recognized home decor pieces, but there is so much more.

“I’ve had probably one of the busiest years,” the artist says in late December before ticking off a lengthy list of projects big and small that have recently occupied his time, ranging from a 6-foot cross for LeBron James’ alma mater St. Vincent-St. Mary High School to a 12-foot steel sculpture he designed for a family in Hudson. “I am quite disciplined in getting things done.”

Don Drumm’s grandfather was a blacksmith and his father was a mechanic, but working with metals wasn’t the life the artist envisioned for himself while growing up in Warren, Ohio. He was born in 1935 during the heart of the Great Depression, and even though his family lived in town, their home had a livery stable out back where Drumm’s father kept a pony and other animals for his children to enjoy.

“You could get away with some of that stuff then,” says Drumm. “The war came on and my father bought an incubator to hatch chickens. I don’t know where he got the eggs, but every 28 days or so, out came these chicks. And it was a wonderful experience. My sister and I would help the chicks crack out of their eggs.”

The family moved to rural Trumbull County during Drumm’s senior year in high school, and following graduation he enrolled at Hiram College with the hopes of becoming a veterinarian.

“I was getting through everything, but I was very dyslexic and left-handed and the whole bit,” Drumm says of his freshman year. “The last term, I had calculus, and I hit that like a brick wall. … We had three days to change whatever we wanted to take. So I ran around, and I found this art class up on the top floor of this one building. I thought, oh man, they’re having fun. I’m going to do this.”

The following year, Drumm studied art at Hiram, but an instructor suggested he’d get a better art education at a different school. He transferred to Kent State University where he earned his bachelor’s degree and then began work on his master’s in sculpture, using his father’s barn as a space to create his thesis project.

“He let me use it one summer to build this big seed pod-like shape that was going to hang in the library,” Drumm recalls. “The thesis adviser liked it, but he still required written documentation and that killed me. In fact, they gave me an extra quarter, and I still didn’t get it done.”

Around this time, Drumm also began working for Smith, Scherr & McDermott, a local industrial design firm that needed a sculptor to do some model work. He was there two years — meeting people and gaining insight into methods that would shape his art, including the sand-casting process for which he is known.

“It seemed almost, not primitive, but very basic,” he recalls of his early experiences with the method in which a design created in sand is used to make a mold for casting metals and other materials. “I could carve into the sand. … And I had no problem carving in the reverse.”

But in April 1960, the industrial design firm’s business changed focus, and Drumm was laid off. It happened the same month he and Lisa married.

“It was the best thing that ever happened,” he says of losing the job. “But when you’re young and starting out — when you’re 25 — you’re in a panic.”

Lisa was a teacher, which provided the couple an income and gave Don the time to figure out how to make art his career. He jokes about it now, but the gratitude for his wife’s support couldn’t be clearer. “I advise any young artist who wants to know how to get started to find somebody that can support you for a couple years,” he says with a laugh.

***

“Life goes and you sort of pick and choose, and things are thrown at you, and you decide what you’re going to or not going to do,” Drumm says when asked about his career path. “It just sort of happened.”

The 1960s were a time of growth for both his art and family. After Drumm’s time at Smith, Scherr & McDermott, he rented his first foundry space, completed his master’s degree at Kent and had three daughters with Lisa.

In 1965, he became the artist in residence at Bowling Green State University. Reporting to the school’s president, William Jerome III, the young artist created sculptures and other art for the campus and took on one of his most monumental works — designing the sandblasted facade for the school’s library — an abstract, indoor/outdoor, 10-story piece.

Two years into Drumm’s six-year Bowling Green residency, he was asked to design a sculpture at his alma mater, Kent State. Solar Totem, a 15-foot-tall piece with more than 100 steel tiles was installed outside Taylor Hall.

Don Drumm was an artist in residence at Bowling Green State University from 1965 to 1971. He made this piece for the administration building. (photo courtesy of Don Drumm)

Three years later, on May 4, 1970, a campus standoff with the National Guard resulted in the shooting deaths of four students, and Drumm’s steel creation became forever linked to the tragedy. “One [student] was killed right by my sculpture,” he says somberly.

Drumm was at Bowling Green at the time of the shootings, but three days later he was in Kent upon the request of the Akron Beacon Journal. “[They] called me to go look at the piece … to see if I could tell which way the bullets came from. ... I was damn near crying all the time I was there. It was a little too personal to me.”

The metal where the bullet pierced the sculpture was splayed outward, facing where the National Guard had stood, leading to a theory that the guardsmen had been fired upon. Drumm brought a piece of metal like the one in the sculpture, and the newspaper hired a marksman to replicate the shot that pierced it.

“To our surprise, the splayed out area was the entry hole,” says Drumm. “We were able to prove that the bullet came from the guard toward the students.”

The following day, he returned to Bowling Green for a send-off for university president Jerome. During the event, a student asked Drumm if he’d consider creating a memorial to the four Kent students. “Dr. Jerome walked up and asked what the student wanted,” recalls Drumm. “I explained and he said, ‘Let that be my last gift to Bowling Green.’ ”

Drumm began designing a 12-foot sculpture with the same type of metal he used in Kent. While he was working on it, state troopers in Mississippi killed two student protesters at Jackson State University. Drumm titled his sculpture Bridge Over Troubled Water: A Memorial to the Kent Four and Jackson Two.

***

The mountains of North Carolina cradle the Penland School of Crafts, and starting in the 1960s, Drumm and his family spent a portion of 14 summers there. Lisa taught fiber arts, and Don taught sculpting, welding and casting. Instructors were brought in for one-, two- or three-week sessions each summer.

“It was a great growth period for myself and my family, being away from the city and experiencing this other life and being involved with the people there,” says Drumm, whose three daughters all spent time at Penland as kids.

The school drew talented artists and craftspeople from across the country. At one point or another during his time there, Drumm recalls teaching alongside furniture designer Sam Maloof, renowned glass blower Dale Chihuly and many more masters of their respective mediums.

“Everybody down there had a profound influence on everyone else,” says Drumm, adding that the exchange of ideas and philosophies was at the very heart of the school’s concept. So much so, that Penland’s second director, Bill Brown, removed all of the cafeteria’s rectangular tables and replaced them with round ones to facilitate interaction.

Leandra Drumm, Don and Lisa’s youngest daughter, has fond memories of those weeks surrounded by artists.

“We grew up in the era of the hippies,” she says. “I have this forever image of [my father] with his wild beard and giant belt buckle and bell-bottoms,” Leandra recalls. “I remember, specifically, my father’s workshop was pretty much a foundation with a ceiling and no walls. It was an outdoor foundry. He was up on the hill, and we were able to come up and visit it. One of my earliest childhood memories is of him teaching me how to make small animals out of copper.”

Leandra is now an artist herself, and the way she sees it, her dad was influenced by his own father, who had a skill for inventing elaborate contraptions for kids to play on at the rural lake resort he owned in his later years.

“What we remembered as kids was he had taken parts from a carousel and put them on mechanical arms that looked liked spider arms,” she says. “This machine would go around and the arms would lift up and down.”

Given his father’s background, it makes sense that Drumm became intrigued by industrial processes such as sand-casting and working with metals like aluminum — an artistic medium he is credited with helping pioneer. For some of his larger pieces, such as his Kent sculpture, he worked in Cor-Ten, a steel that weathers over time and is seen in the rugged exteriors of railroad boxcars.

“I feel like I’m part of an industrial age and should be using as many of those techniques as I can,” Drumm says. Over time, that meant trading works crafted by a cutting torch for ones born of exacting, computer-controlled cutting devices, which allowed him to bring his larger pieces new detail and dimension.

“He has these mechanical skills on top of the sculpting,” Leandra adds, “how things can be assembled and how they work together and how to create something that can last. I think some of that mindset of how to take things apart and how to put them back together came from my grandfather.”

***

Garden of Fantasy is located inside Akron's Jean and Milton Cooper Cancer Center. (photo by Jerry Mann)

The Don Drumm Studios & Gallery is tucked away on Crouse Street in Akron. What started as a single structure when Don and Lisa first opened the place in 1971 has now grown into a series of buildings, which house galleries featuring not only Drumm’s works but pieces by many other artists from across the nation.

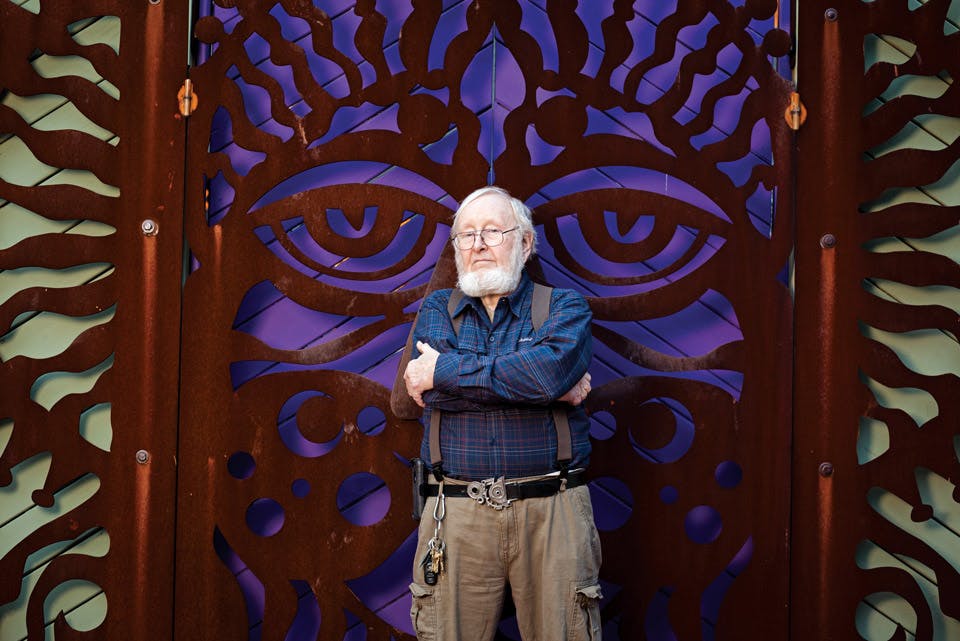

Those familiar with Drumm’s art instantly note his handiwork in the huge steel doors that serve as the gate to the gallery’s entrance. The courtyard just beyond it is filled with cast-aluminum suns and other works. He built his galleries’ interior spaces and decorated their whimsical exteriors, but Don says this place is all Lisa’s. While he has spent years creating, she built the family name into one that is synonymous with beautiful and functional art pieces for the home.

“They have been a pair forever,” notes E.J. Thomas Hall’s Daniel Dahl, who counts the Drumms among his friends. “Lisa taking care of Don in every way ... is what has let them grow as a couple and with the gallery and in getting his work all over the country.”

Drumm enjoys the fact that he’s known for large-scale public art, as well as for designing home decor pieces and kitchenware such as bowls and measuring cups. Those dual pursuits do not conflict in his mind. Leandra says they have been vital to her parents’ success.

“One of his advantages is he is both a sculptor and a craftsman,” she explains. “He’s known on two different levels, but when times were lean the sculpture work helped subsidize the growing gallery.”

Drumm is around Crouse Street most days, but he’s usually tucked away in his studio working on designs that he’ll eventually send to artists he works with in North Carolina, who’ve done the bulk of his fabricating work for the past decade and a half, as well as the three foundries that cast his functional pieces. That act of creating pieces true to his vision is still Drumm’s driving force.

“I don’t know how I want to be remembered or if it’s even important,” he says. “I never went looking for the museum, and you won’t find many of my pieces there. My thing is to do the best I can and maintain my own identity.”

Related Articles

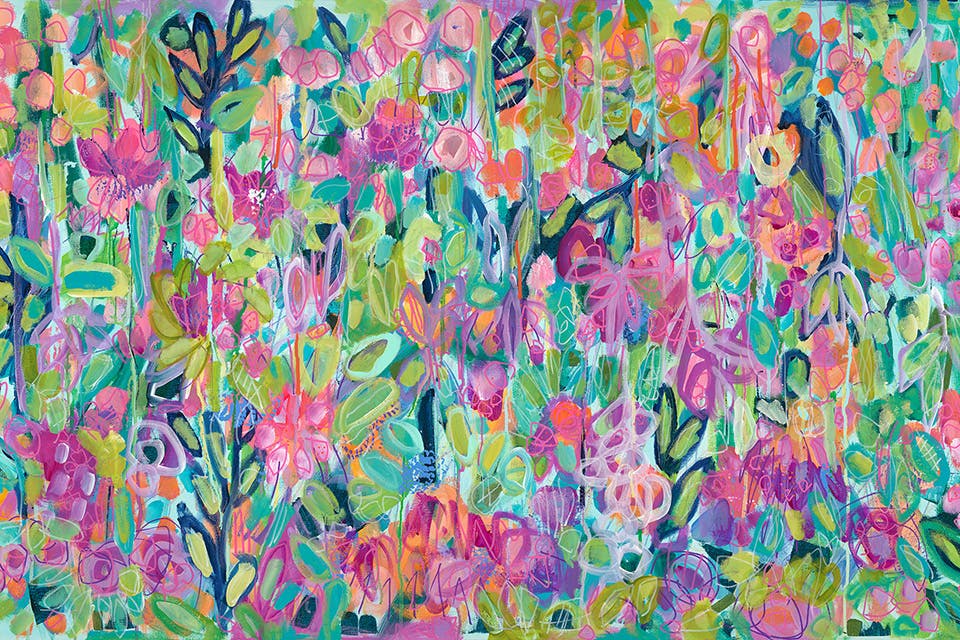

Flowers Power Alisa H. Workman’s Beautiful Paintings

The southwest Ohio-based artist embraces spontaneity in creating her floral-inspired canvases. READ MORE >>

View a Whimsical Cloth Circus at Canton Museum of Art’s ‘Without a Net’

California-based artist Susan Else’s vibrant and fun creations are the focus of this exhibition, which runs from Nov. 21 through March 3. READ MORE >>

The Sculpted Visions of Alan Cottrill

The artist’s cast-bronze works are found across Ohio and far beyond. We visited his Zanesville studio to learn about his process and the road that led him to finding his passion. READ MORE >>