How Union Terminal Became an Iconic Cincinnati Landmark

It opened in 1933 as one of the nation’s most magnificent train stations, but Union Terminal’s closure in 1972 cast doubt over the beautiful art deco building’s future. Then, Superman and, years later, Hamilton County voters saved the day.

Jan./Feb. 2025

BY Jim Vickers | Photo courtesy of Cincinnati Museum Center

Jan./Feb. 2025

BY Jim Vickers | Photo courtesy of Cincinnati Museum Center

The opening of Cincinnati’s Union Terminal came late in the railroad era for such a magnificent structure, but there was no evidence of such concerns during the building’s public dedication on the afternoon of March 31, 1933 — four years after construction began and nine months ahead of schedule.

Cincinnati Union Terminal Co. president H.A. Worcester presented Mayor Russell Wilson with a ceremonial gold key in front of a crowd of tens of thousands. The exchange was preceded by a parade and music by Frank Simon’s Armco Band. Then, at 3 p.m., the doors of the terminal opened, and the public was invited in to see the place for themselves.

“We tried to build something new, fresh and joyous,” Col. Henry M. Waite, Union Terminal’s chief engineer, told Rotary club members gathered at the new station for a meeting the day before the public dedication.

Aside from the excitement surrounding New York-based architectural firm Fellheimer and Wagner’s design, the new station helped solve a real problem: When the Ohio River flooded, it put Cincinnati’s existing railroad stations underwater. Union Terminal’s location on the city’s west side was above the Ohio River’s high-water mark.

The $41 million project encompassed not only the beautifully appointed, art deco terminal with its half-dome facade and park and fountain out front, but also outbuildings and railroad tracks leading to the station. Spanning 287 acres, 22 separate buildings and 94 miles of track, the site served seven different rail companies and could accommodate 216 trains and 17,000 passengers daily. Yet those monumental numbers were quickly rivaled by reports of the exquisite beauty found within the terminal.

Beyond the station’s soaring dome that rises 106 feet above the lobby floor, artistic touches throughout the sprawling space were marveled at by those who got a first look. Reporter Cherry Greve provided an account in the March 25, 1933, edition of the Cincinnati Times-Star.

“To attempt a description and discussion of the new Cincinnati Union Terminal in its entirety is an impossible feat,” Greve wrote. “To restrict the discussion to the artistic viewpoint is necessary and even here the task assumes momentous proportions.”

Artist Winold Reiss created mosaic tile murals for Union Terminal’s lobby, one that depicts the history of the United States through people and another that shows a timeline of Cincinnati from settlement to the 1930s. (photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

The article delved into the work of artist Pierre Bourdelle, who created murals for the walls of the terminal’s movie theater, lunchroom and private dining rooms, as well as a variety of low-relief linoleum works for the walls, including an intricate jungle scene in a waiting alcove. The report also mentioned Winold Reiss’ mosaic murals in the lobby and concourse and artist Maxfield Keck’s bas reliefs of “Transportation” and “Industry” carved into the building’s facade.

“The Cincinnati Union Terminal is more than a mere terminal,” Greve wrote. “It is a work of art embodying all that is finest in the various fields of art and science known today.”

Despite its allure, there was no avoiding the fact that Union Terminal’s fate depended on the popularity of trains as transportation, and by the time it opened, ridership was already waning. On the evening of its public dedication there was at least one concern briefly voiced about the future of train travel. During a dinner at Cincinnati’s Netherland Plaza hotel, former West Virginia Gov. John J. Cornwell delivered remarks that, while congratulatory and hopeful about Union Terminal’s future, contained some straight talk that proved prophetic.

“I should say [the terminal] came after the need, to some degree, had passed,” he noted, “for the decline of more than 50 percent in railroad passenger business has left expensive passenger stations in this country standing as monuments to civic spirit and unfulfilled railroad expectations.”

***

Driving down the long entrance road, Union Terminal stands out, instantly recognizable in the distance. Although clearly of another time, it remains imbued with the energy and vitality with which it was created. Large swaths of green flank the roadway and lend an air of grandeur and importance that carries through as you park, pass the elaborate fountain out front and enter what is now the Cincinnati Museum Center.

For a first-time visitor, the large lobby prompts an immediate moment of pause in order to take it all in. The concentric rings of the massive half dome glow in shades of orange and yellow. Just below them, Reiss’ mosaic murals stretch from one end of the rotunda to the other in separate 22-by-110-foot sections. One depicts the history of the United States through people, from Native Americans to industrial workers of what was then the modern era. The other presents figures against a timeline of Cincinnati from settlement to the 1930s.

The Cincinnati History Museum, The Children’s Museum, the Museum of Natural History & Sciences and the Nancy & David Wolf Holocaust and Humanities Center, along with the Cincinnati History Library and Archives and an Omnimax theater, are all located here.

Walk down one main hallway for a trip into Cincinnati history, including a massive model-train display that depicts the city’s downtown in the 1940s. Another hallway leads to a dinosaur hall, an immersive Ice Age exhibit and a journey through a cave built inside the museum. Other treasures within the building include the Rookwood Ice Cream Parlor (formerly a tearoom) and its tile installation crafted by Rookwood pottery artist William E. Hentschel. Seeing it all is hours of fun, but it took years to figure out the building’s best use. Once that was decided, operating expenses and later repairs that proved necessary to ensure the building’s long-term survival created daunting new challenges.

As early as the 1960s, it was becoming clear that Union Terminal’s time as a train station was coming to an end. Ideas for other uses — some serious and others not so much — were bandied. In 1968, science exhibits were put on display, but they only remained a couple years. By the time of Union Terminal’s last day of operation, Oct. 28, 1972, just two trains came through the station.

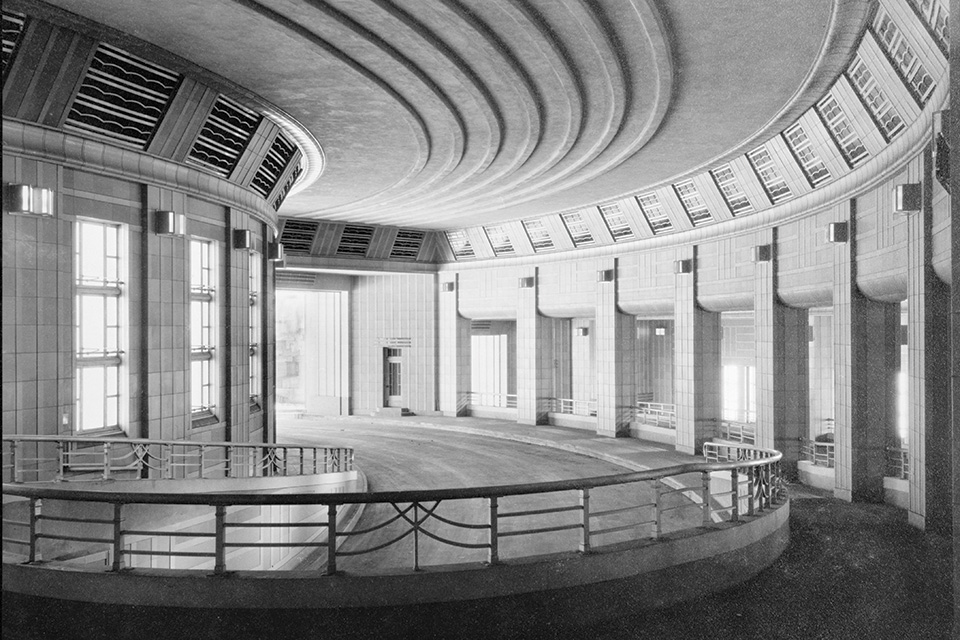

In 1972, the once-bustling Queen City landmark closed its doors and sat empty. This photograph was taken after train service stopped but prior to the building’s revival during the 2000s. (photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

It wasn’t long before threats to the building began to appear, along with a grassroots effort to save it, including a song called “Save The Terminal” recorded by then-Mayor of Cincinnati and future talk show host Jerry Springer.

In 1974, a decision to make way for double-decker freight trains led to the demolition of the station’s 450-foot-long concourse, which held 16 Reiss mosaics depicting industrial workers as well as the artist’s large mural of North America. (The mosaics of workers were relocated, but the map could not be.) The station’s grand rotunda was saved but for what purpose nobody was sure. Then, talk of razing the building began to circulate due to the liability of such a large vacant space. The Cincinnati Union Terminal Co. was seeking $1 million for the property.

“If we can’t sell it, we’ve got to tear it down,” Cincinnati Union Terminal Co. lawyer John Hudson said in a United Press International article that appeared in the Jan. 19, 1974, edition of The Coshocton Tribune. “The cost of maintaining it and the taxes are just tremendous. If it can’t be sold, it’s got to be disposed of.”

A year later, the city of Cincinnati paid $1 million for the 15-acre site and $2 for the building to find a new use for Union Terminal. It heard pitches from three developers, including the Columbus-based Joseph Skilken Organization, which pitched an entertainment and shopping concept it referred to as “Oz.”

“People will come into the center rotunda, where we’ll have an ice-skating rink a la Rockefeller Plaza,” then-company secretary Steve Skilken detailed in a report on the Associated Press wire that appeared in the Jan. 8, 1978, edition of The Lima News. “Around the rotunda area will be a lounge, fast food shops, a fine steak restaurant, a crepe restaurant.”

The development opened in 1980 as a shopping center with 40 stores. All but one tenant had moved out by 1985.

***

Just as Union Terminal faced a period of uncertainty, it got a second life via pop culture in a most unexpected way. In September 1973, when the Hanna-Barbera cartoon “Super Friends” appeared in the Saturday-morning lineup, the headquarters for Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman and the crew looked just like Cincinnati’s landmark train station.

The resemblance between the superheroes’ headquarters and Union Terminal was anything but coincidence. Cincinnati-based Taft Broadcasting Co. owned Hanna-Barbera from the late 1960s through 1992. In 2009, Hanna-Barbera background artist Al Gmuer said during an interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer that when he sent his sketch for the Hall of Justice to the network for review it “had more windows,” but they changed its design to more closely resemble the Cincinnati landmark.

“In the long run, I hated that building,” Gmuer told reporter Alex Shebar for the March 25, 2009 article. “The way it’s designed, it was not easy to draw. I had nightmares about that damn building.”

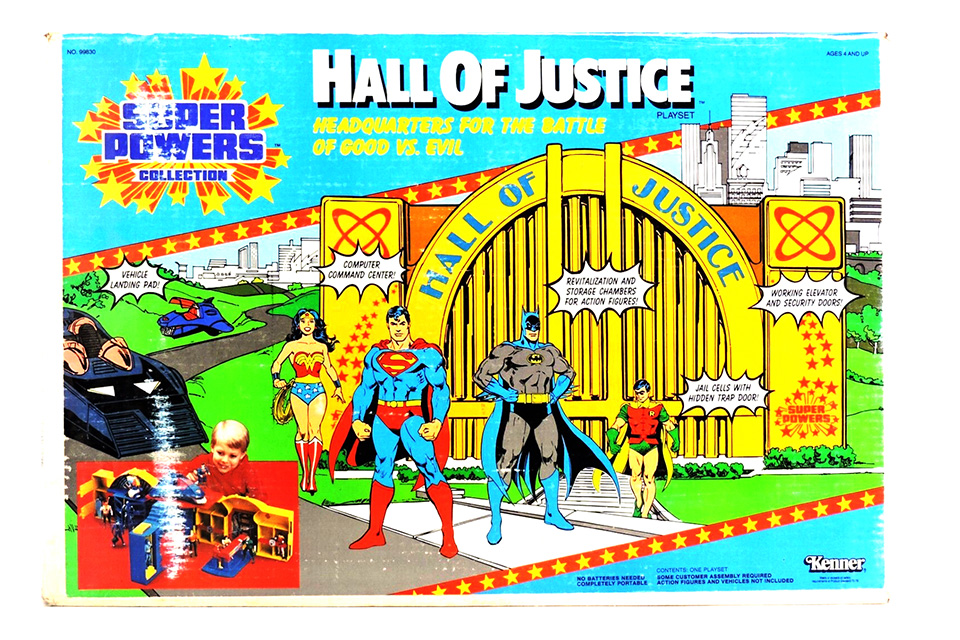

The Hall of Justice in Hanna-Barbera’s “Super Friends” cartoon bore a striking resemblance to Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, which carried through to toy lines created around the long-running series. (photo from actionfigure411.com)

The Hall of Justice in Hanna-Barbera’s “Super Friends” cartoon bore a striking resemblance to Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, which carried through to toy lines created around the long-running series. (photo from actionfigure411.com)

“Super Friends” ran from 1973 through 1985, and while the show evolved, the Hall of Justice remained, making Cincinnati’s landmark visually synonymous with truth, justice and the American way with legions of superhero fans, even if they wouldn’t make that connection for years to come.

Such goodwill didn’t hurt as plans progressed to find a new permanent use for the structure. In 1986, Hamilton County voters approved $33 million in funding to turn Union Terminal into a cultural center. In November 1990, the Cincinnati Museum Center opened and marked the beginning of the building’s life as one of the city’s cornerstone attractions. (Amtrak restored rail service to the building in summer 1991 and still operates there today.) In 2004, county voters approved a levy to cover operating costs and capital repairs and then approved an extension five years later, but that wasn’t the end to the challenges.

The ultimate threat facing Union Terminal was time. In 2014, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named it one of the 11 most endangered historic places in the United States due to deterioration, water damage and mechanical needs that carried a staggering cost of $212 million to fix. That same year, Hamilton County voters approved a quarter-cent sales tax increase over five years to generate $170 million toward that repair bill. The Cincinnati Museum Center closed in July 2016 and reopened in November 2018 with a repaired and renewed building and experience.

Renovations and improvements completed in 2018 revived Union Terminal, bringing the art deco landmark back to its original grandeur. (photo by Matthew Allen)

Superman still has a place here too. When director James Gunn’s new “Superman” movie came to town in summer 2024, Union Terminal was one of the filming locations. A flag bearing the seal of the city of Metropolis was spotted over the Cincinnati Museum Center on July 18, 2024, leading many to reason that the Hall of Justice makes an appearance in the film, which is set for a July 11, 2025, release.

As Robert Thompson, director of the Bleier Center for Television and Pop Culture told the Cincinnati Enquirer for its 2009 story about the connection between Union Terminal and the Hall of Justice, the building’s relative anonymity on a national level made it appealing for the superhero realm. It also explains our continued fascination with it.

“Someone knew of a great building with a wonderful visual look that reeked of the power and the energy it was designed for,” Thompson said. “It also wasn’t overused like, for instance, the Chrysler Building. It wasn’t a cliche.”

For more Ohio history, sign up for our Ohio Magazine newsletters.

Ohio Magazine is available in a beautifully designed print issue that is published 7 times a year, along with Spring-Summer and Fall-Winter editions of LongWeekends magazine. Subscribe to Ohio Magazine and stay connected to beauty, adventure and fun across our state.

Related Articles

New Book Details Origins and Evolution of Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park

The destination’s vice president of museum operations Alex Heckman and curator Steve Lucht wrote the 222-page, hardbound coffee-table book. READ MORE >>

Two Ohioans Appear on the Hallmark Channel’s ‘Finding Mr. Christmas’

This holiday-themed reality show searches for the next Hallmark star, and Ohio natives Marcus Brodie and Logan Shepard are among the contestants this season. READ MORE >>

‘Ohio: Wild at Heart’ Now Showing in Select Theaters Statewide

Produced in partnership with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, this film showcases some of our state’s most striking natural features. READ MORE >>