Our Last Interview with American Icon John Glenn

John Glenn was born on July 18, 1921, in Cambridge, grew up in neighboring New Concord and became an American hero as astronaut and U.S. Senator. We last sat down with him in 2005.

December 2016 Issue

BY Jennifer Haliburton | Photo courtesy of NASA

December 2016 Issue

BY Jennifer Haliburton | Photo courtesy of NASA

Editor’s Note: In 2005, we sent staff writer Jennifer Haliburton to interview John Glenn about his work to improve education for children in our state. The resulting story, which originally ran in our September 2005 issue, reminded us all that national heroes are a rare commodity, especially ones who live their convictions the way John Glenn did. We hope you enjoy this look back at the life of our former senator and fellow Ohioan.

John Glenn is waiting for news.

He doesn’t let on: no signs of nervousness, not even a hint of rushing his visitor. He just sits patiently behind his desk, occasionally twirling his eyeglasses, politely answering questions about his least favorite topic, himself — and waits for the news.

It’s a warm, sun-drenched July day on the campus of The Ohio Sate University and inside Page Hall it seems even brighter. The light pouring in through the window of the former senator’s cozy office is part of it; the rest comes from an upbeat air that gives this place, the John Glenn Institute for Public Service & Public Policy, the enthusiastic feel of a campaign headquarters — from the smiling young people milling about the building to the presence of Glenn’s cheery chief of staff and scheduler, perched right outside his office. Glenn adds to the sunny campaign-trail aura. He greets guests with a smile and a handshake and is prone to throwing out a “hey, how are ya?” or “take it easy” to passersby. His ensemble is standard-issue for senators, past and present: the immaculate navy blazer with shiny gold buttons, the dark red tie emblazoned with the Bill of Rights (“We the people” nicely visible beneath the knot).

Like a Washington insider, too, Glenn will be on one of the Sunday talk shows a few days from now. In the wake of the news that lumps of foam debris fell off of the space shuttle Discovery when it launched a couple of days ago — the same thing that caused the shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003 — the news media is abuzz with questions: What is the future of the shuttle program? How relevant is space flight anymore? And is it worth all the risk?

Here is where Glenn differs from other political figures: There is no mistaking that John Glenn is not just a former senator. He is a living legend. While most Americans have a special reserve of skepticism for the utterances of politicians, John Glenn they’ll believe. They believe him when he says that yes, being an astronaut is a risky occupation, but one doesn’t go into the business of riding a rocket into the cosmos at some 20 times the speed of sound without understanding the dangers involved; and yes, it is worth the risk, because it’s imperative that this country maintain its claim as the leader of new frontiers and scientific research. They won’t question him.

The public knows that John Glenn, the embodiment of gravitas, has earned the label of national hero several times over, and at 84, has carried the title for longer than many people have been alive.

“Excuse me,” says Glenn’s longtime chief of staff, Mary Jane Veno, materializing in the doorway. “They docked. They docked perfectly.”

This is the news he’s been waiting for, word that Discovery — the same shuttle he boarded in 1998, making him the oldest person ever in space — has successfully connected with the International Space Station.

“Oh good, good,” says Glenn. “I’m glad to hear that.”

Suddenly Glenn is far from being a politician or a hero — he's Bud from New Concord (as the folks there remember him), an aeronautics fanatic who’s had a thing for flight ever since the day in day in 1929 when his dad, John Herschel Glenn Sr., pulled over to the side of a grass-field airport during a drive to Cambridge, saw that a pilot was offering rides aboard an open-cockpit airplane, turned to his 8-year-old son and said those six magic words: “You want to go up, Bud?”

“Hey MJ, have they sent any more expanded pictures down of the protective tiles? That’s what they’re gonna take pictures of when they’re belly up to the station, you know,” Glenn says to Veno The more he talks about space, the more clearly it seems those youthful, all-American features come into focus: the deep dimples, the still reddish-blond eyebrows, the freckles. (Author Tom Wolfe once called Glenn’s “the sunniest face in 10 counties.”)

The former astronaut knows that now that Discovery and the enormous space station are linked, they'll be as bright as a first-magnitude star, visible to the naked eye in the night sky above his downtown Columbus apartment. NASA’s web site provides schedules instructing on the best viewing times and where to gaze.

“Can you get [a schedule] for the next l0 days? Probably for the whole flight?” he asks Veno, who disappears again.

John Glenn wants kids in schools across America to feel this same mixture of insatiable curiosity and fascination about the galaxy. Unlike during the space race of the 1960s, teachers no longer regularly wheel a television set into their classrooms, allowing kids to sit spellbound in front of images of astronauts rocketing off the earth. Still, says Glenn, students should be steeped in the sound math and science education that prepares them to appreciate the wonders of space, and necessary to become an astronaut.

He knows, too, that the solid values and constant encouragement to explore that he received in New Concord are responsible for his own accomplishments, and he and a band of dedicated citizens in his hometown are determined to share those virtues with another generation, inspiring them to reach the same heights.

“I talk a lot about that these days,” says Glenn. “I think it is so key to the future of our country.”

The fact that he is in the middle of his ninth decade is hardly a deterrent from this lofty task; age certainly hasn’t stopped him before. At 37, Glenn was the oldest of the famed Project Mercury test pilots turned astronauts chosen as the first Americans to explore outer space (famously chronicled in Tom Wolfe’s book and the movie, “The Right Stuff”). At 71, Glenn was re-elected to a fourth term as Ohio’s longest-serving senator, and he still ranks as the only state politician to win all 88 of Ohio's counties. And, of course, at 77, Glenn’s tenacity alone was responsible for his second trip off the planet.

Not that the achievements made at a mature age make Glenn want to rhapsodize on the joys of getting older.

“For all the advances in science and medicine that I have supported and that have occurred in the 35 years since my orbital flight, one immutable fact remains: There is no cure for the common birthday,” he once told a crowd at his alma mater, Muskingum College.

His visitor has forgotten this anecdote. She makes the mistake of wishing Glenn a happy belated birthday (He turned 84 on July 18.)

“I’m trying to forget about them,” Glenn says with a grin.

***

John Glenn and his wife, Annie, ride in a 1998 parade honoring U.S. astronauts in Houston, Texas. (photo courtesy of Library of Congress)

December 13, 1962

Dear Mr. Glenn,

I would like you to know that you are my number one hero. Everybody says I picked a dandy person. …

The letters seem endless.

Dear Mr. Glenn,

I, a boy of twelve, sometimes wonder how it feels to be a great nan of the nation ...

There are roughly 25,000 of them. There used to be about a quarter million more such letters.

One day seven years ago, three large semis pulled up to The Ohio State University Archives, more than 2,000 boxes of John Glenn’s material in tow. Jeff Thomas, Glenn’s archivist at the university, narrowed it all down by taking just a sampling of the fan letters, and thus slimming the collection down to about 1,000 meticulously organized, slate-gray boxes, all now neatly sacked in a chilly, climate-controlled warehouse with 30-foot ceilings and forklifts navigating the aisles of what is, essentially, John Glenn's attic.

“That's what you get for growing up in the Great Depression — you learn not to throw anything away," says Glenn, an admitted pack rat. Though much of the material in the OSU collection was previously stored at the Library of Congress, plenty of it comes straight from John and Annie Glenn's other home in Bethesda, Maryland.

It’s difficult to imagine these days — when even those too young to have experienced much already seem a bit jaded — but only 43 years ago, a generation of children were so thrilled by the accomplishments of one person and so proud of the United States’ success, that they took pencil to paper and poured out heartfelt emotion, unselfconsciously calling John Glenn their hero.

“They were coming in by the sack load every day,” says Glenn, who in 1964 compiled some of the most touching and eccentric letters in a book called P.S. I Listened To Your Heartbeat. He notes that NASA had to create a special mailroom just to manage the flood of correspondence from admiring kids after he became the first American to orbit the earth. “And they all got answers back, we made sure of that.”

As enamored as Glenn was of airplanes as a boy, he could have written the same type of letters to one of his childhood heroes, Charles Lindbergh. Fortunately for him, his father, the owner of a small plumbing business, shared his interest in flying: He’d been captivated by the planes dog-fighting overhead while an infantryman in France during World War I. So, he went up with his 8-year old son for that flight in the open-cockpit airplane over Cambridge, the one that immediately left Glenn amazed by flight.

“Looking down at everything on the ground from way up there — I was fascinated by aviation from that time on,” says Glenn. “I started building all these model airplanes. [And since] my dad was interested in them too, every year we’d go up to Cleveland for the National Air Races — camp out the night before, then go watch the races the next day.”

Glenn has nothing but affection for the close-knit, patriotic, Muskingum County community he was raised in and still frequently visits. “Sometimes it seems to me that Norman Rockwell must have taken his inspiration from New Concord, Ohio,” he wrote in John Glenn: A Memoir.

A boy could not have had a more idyllic early childhood than I did.”

But when the town asked to use the large home his father built for the family in 1923 to honor Glenn’s achievements, he had reservations. “I gave it to them on one basis: I didn’t want it to just be some Glenn museum. We can do without that,” he says.

“But,” he adds, “if the place could be used as an inspiration to kids and to educate them on what things were like when we were coming up, then that’d be something worthwhile.”

Which explains why Lorle Porter, standing inside the gray-and-white home now called the John and Annie Glenn Historic Site and Exploration Center, is wearing a prim, old-fashioned housedress, crafted from a 1944 McCall’s pattern by local seamstresses. She plays Glenn’s mother, Clara, in the living-history portion of the house, where everything from the ration books to the radios — not to mention the display of John Glenn’s military uniforms — is authentic.

“The younger people don’t know about any of this. It’s as disconnected from life today as the l8th century is from The Jetsons,” Porter says with a sigh. The retired Muskingum College history professor, author of several books on Ohio and living-history coordinator at the center, says the goal of the site is to convey the types of sacrifice, values and sense of civic responsibility that had Glenn’s father doing plumbing jobs in exchange for food during the Depression, and sparked Glenn to immediately enlist in the Navy after learning of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

“People can’t believe that you ever had ration books, that you once had to sacrifice to that extent,” says Porter. “The last time Annie and John were here, Annie said, ‘The kids today need to know these things.’ ”

***

Astronaut John Glenn gives a double thumbs-up as he and President John F. Kennedy arrive at the Cape Canaveral Missile Test Annex in Florida. Glenn's Mercury Atlas 6 mission lifted off from Launch Complex 14, in the background, on Feb. 20, 1962. (photo courtesy of NASA)

Annie Glenn enters her husband’s office so quietly that, were it not for the side door clicking shut behind her, she’d have stepped in unnoticed.

John Glenn and his visitor look in her direction as she takes a seat beneath a large multi-colored quilt covering the wall (a gift from West Virginia Senator Jay Rockefeller’s wife after hearing about Annie’s love of folk art).

Glenn smiles broadly at his wife and mentions the view of the docked shuttle Discovery and Space Station they’ll see from the apartment tonight. “Hey, Annie! We’ll have to get the old binocs out,” he says. Glenn curls his fingers and holds them up to his eyes, peering at his 85-year-old wife through imaginary binoculars, and proving that space isn’t the only thing capable of transporting him back to being youthful Bud from New Concord.

Few couples can say they spent time in the same playpen together as children, as Annie and John did when their respective parents, who were close friends, would entertain at each other’s homes. They’ve been married for 62 years, and Annie still won’t let him upgrade the $125 engagement ring he slipped on her finger before heading off for flight training. “It’s a tiny little thing,” says Glenn of the purchase he made at 21, “but Annie’s still just as proud of it as if it were the Hope diamond.”

The Glenns have two children, Dave, 59, a doctor, and Lyn, 58, an artist. Handsomely framed photos of the family decorate the Page Hall office’s bookshelf. The beaming faces make it easy to forget that this close-knit family once struggled to help Annie communicate with the rest of the world. A severe speech impediment left her stammering 85 percent of the words she spoke.

The communication problem never mattered to Glenn. “I would just let her plow through it, let her get all her ideas out,” he says. But the limitations it placed on Annie’s interactions with others were impossible to miss. “The kids would have to answer the phone for her,” he says, “or if she wanted to talk to one of her friends, they’d have to get the person on the phone and then give it to Annie.”

That all changed when she attended an aggressive, three-week course on overcoming stuttering at Hollins College (now University) in Virginia in 1973. The result was a life-changing triumph over a half-century-long onstage. These days, when not in the co-pilot seat of her husband’s twin-engine Beechcraft Baron, working the radio and maps as Glenn pilots the plane between Columbus and Maryland, Annie frequently lectures on speech pathology.

“You know, one of the most moving conversations I’ve ever had was when she called me from Hollins at the end of that three weeks and talked to me on the telephone,”

Glenn remembers. “I mean, over the years, I would always call her whenever I was away. But for her to put in a call, on the telephone, to me, by herself — Glenn pauses for a moment, lifts his hand off his desk, and meditatively strokes the side of his face. “Well, that was just really something.”

Even if John Glenn, Neil Armstrong and Orville and Wilbur Wright had been the only aeronautics notables to call Ohio home, the state would still have a solid claim as the “Birthplace of Aviation.” An astonishing two dozen NASA astronauts have Ohio roots. And in one 1995 shuttle mission alone, four of the five crew members were born in the Buckeye state.

The Glenns and the group at the Exploration Center want to create an atmosphere that keeps the tradition going.

“That's why it’s so important that this is here in southeastern Ohio: It shows the local kids that if someone from this little Appalachian county can do all these great things, you can too,” says Don McKendry, the center’s director and former principal of John Glenn High School. “When you start talking about the great explorers of

American history — Lewis and Clark, Charles Lindbergh — John Glenn is one of them.”

“Over and over again, we try to emphasize to these students, ‘You could be the person that leads us to Mars.’ ”

Meanwhile, Glenn wants to make sure that students are given the right tools to support those aspirations, and that they are surrounded by a nurturing culture that recognizes the importance of such goals.

“If you think about it, there are two basic things that built this country into a leadership position in a relatively short period of time,” says Glenn. “One was education. Not that it had been perfect, but it used to be that a good education wasn’t seen as just being for rich kids, it was for everybody. And the second was basic research. We’d always been at the forefront of learning new things first and putting more money into scientific research than any other country.”

However, Glenn cites the nation’s wealth of independent school boards as inadvertently causing unequal standards of education and not placing enough emphasis on math and science, and both the government and major corporations for not funding research at the levels they once did

“The real thing that's going to provide jobs and a good future for America is having a well-educated citizenry so that we can perform at the same level as other countries, and funding the basic research needed for us to discover new things first. If we lose out on education, we lose out on leadership in the world.”

***

The focus on education is hardly a new path for Glenn, just the continuation of an adventure that has always had public service as its mission — whether affirming the country’s leadership by orbiting the globe, or securing its future prestige by focusing on the next generation.

“When I think of John Glenn I think of three things,” says Tom Daschle, former South Dakota senator, Senate majority leader and a friend of Glenn’s. “First is his aura: The fact that when we were in Congress, he didn’t try to present himself this way, but he was always more than just another senator — he also happened to be this national hero. Second is that he is clearly a man of immense integrity. And third, because of that integrity and because everyone looked at him in this heroic manner, he’s always had to live with very high expectations.

“The remarkable thing is he actually lives up to those expectations.”

Related Articles

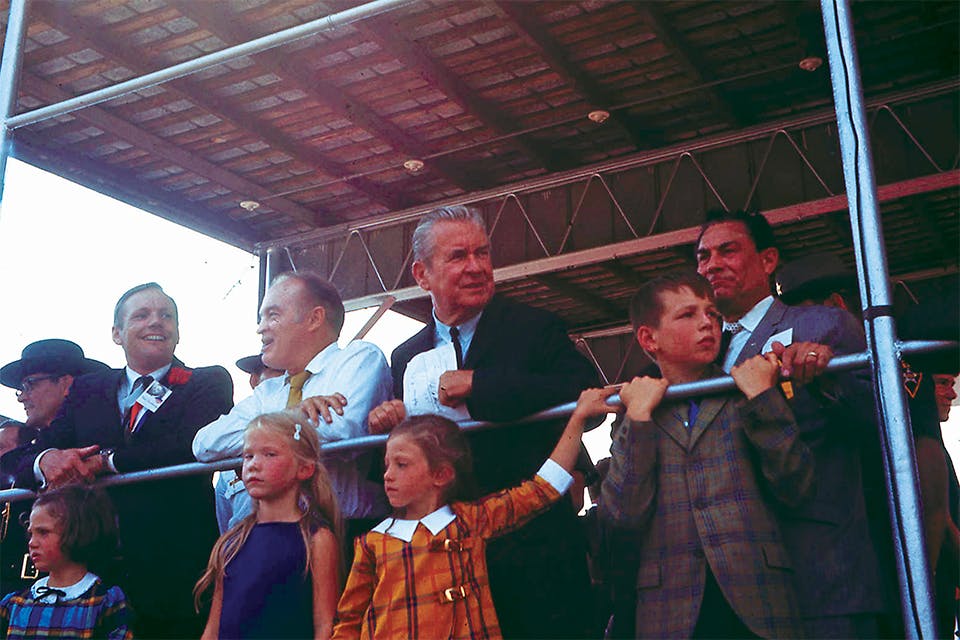

Neil Armstrong Returns to Wapakoneta

On Sept. 6, 1969, the first man to walk on the moon returned to his hometown for a hero’s welcome. Comedian Bob Hope and Gov. James Rhodes joined him. READ MORE >>

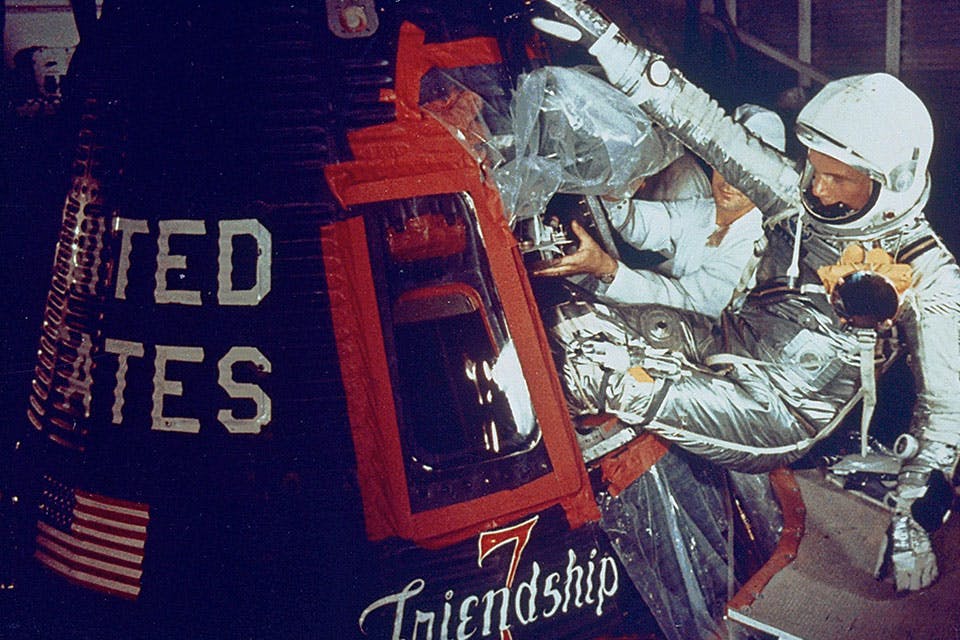

John Glenn Blasts Off

In February 1962, all eyes turned to Ohio as the state celebrated its native son becoming the first American to orbit the Earth. READ MORE >>

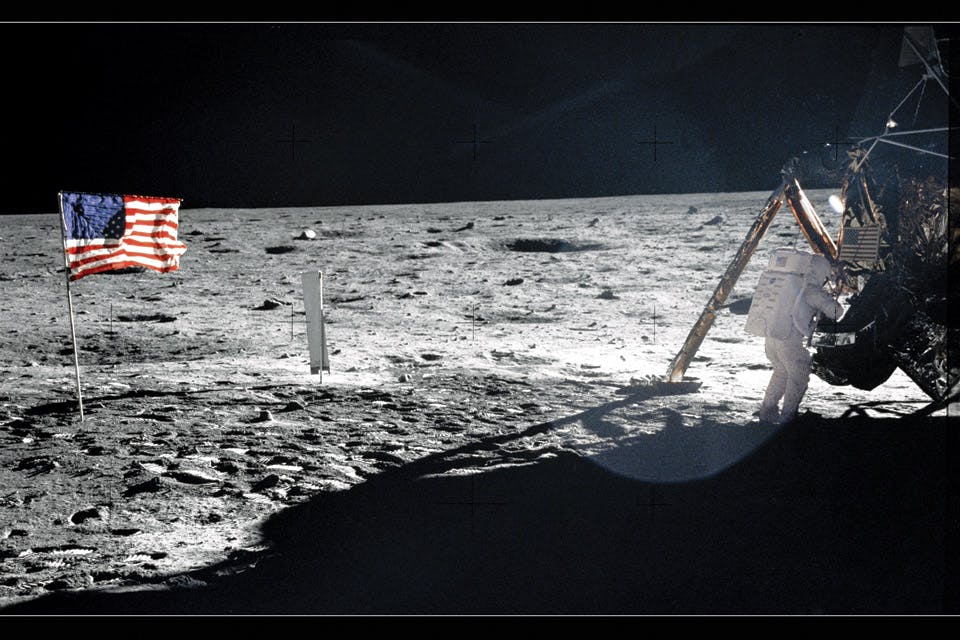

One Giant Leap: The Lasting Legacy of Apollo 11

Ohioan Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the moon July 20, 1969, changing how we look at space and capturing the imagination of people around the globe. READ MORE >>