Ohio Life

Science for Everyone

Stone Laboratory welcomes scientists, students and anyone interested in learning about freshwater problems and solutions.

Related Articles

Explore these Lake Erie Shore Towns and Islands

Ohio’s Lake Erie islands and our state’s northwestern shoreline are full of history, nature and great lakeside towns to explore this time of year. READ MORE >>

The History of the Put-in-Bay Road Race

During the 1950s, this annual event brought sports car owners to South Bass Island to face off on a 3.1-mile course set up on city streets. READ MORE >>

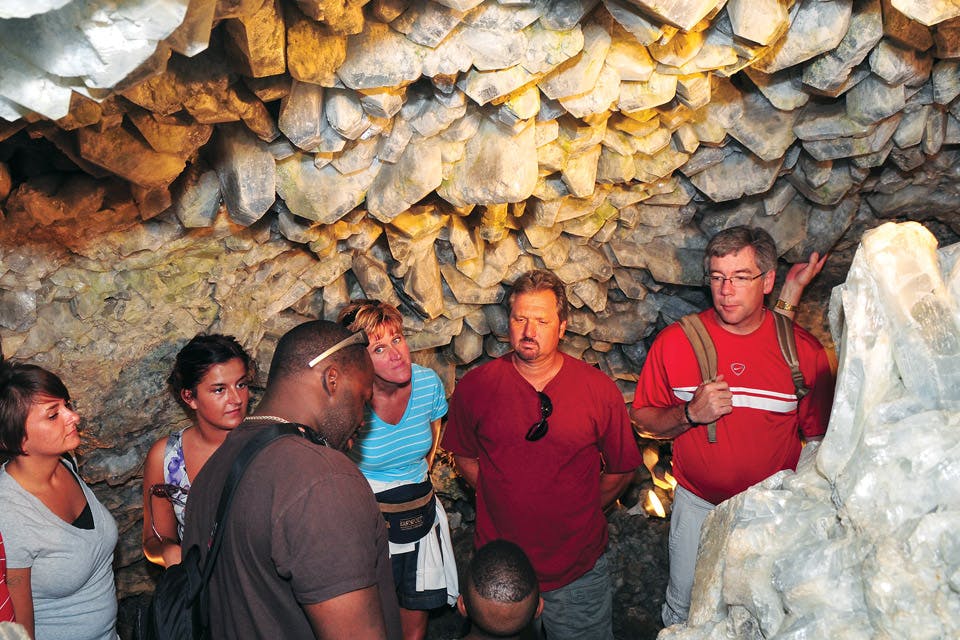

Crystal Cave, Put-in-Bay

Heineman Winery offered tours of what it bills as the world’s largest geode to stay afloat during Prohibition. You can still check it out today. READ MORE >>