How Hollywood’s Warner Brothers Got Their Start in Ohio

Before they launched Warner Bros. Studios, Sam, Albert, Harry and Jack were just the Warner brothers, showing movies across the Mahoning Valley.

February 2017 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photos courtesy of Mahoning Valley Historical Society

February 2017 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photos courtesy of Mahoning Valley Historical Society

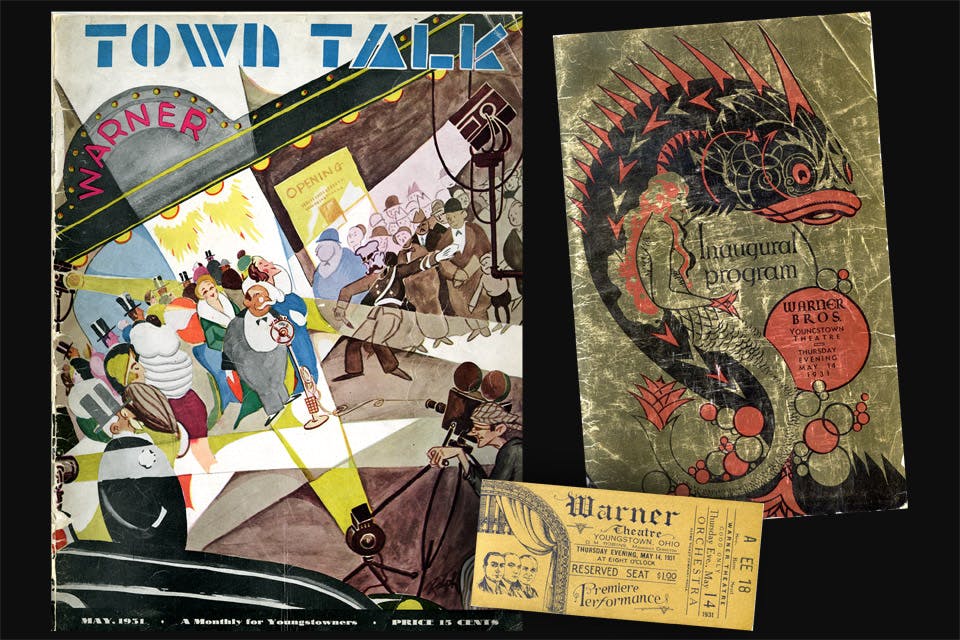

Spotlights scanned the night sky, a brass band performed and one thousand people showed up just to mill around West Federal Street, tying up traffic throughout downtown Youngstown. Untold thousands more listened to the May 14, 1931, party covered live on WKBN radio or read the special edition put out by the Youngstown Vindicator.

Inside, the invitation-only, capacity crowd of 2,500 included men in white tie and tails and women in furs — fitting attire given the opulence they were to see for the first time. The $1.5 million Warner Theatre was opening with a fashion show, organ recital and a screening of the new film “The Millionaire,” but it wasn’t just any theater opening. It was a celebration of how far the venue’s namesake brothers had come. Ben Warner once told his sons, “Together, you are invincible,” and together they proved it.

Long before the Warner brothers were Hollywood players, Sam, Albert, Harry and Jack traveled across the Mahoning Valley showing movies. They opened their first theater just across the state line in New Castle, Pennsylvania, before setting off for Pittsburgh, New York and then, in 1917, California to make movies themselves.

In 1926, the brothers’ studio presented “Don Juan,” the first feature-length film with synchronized sound effects and music. A year later, it released “The Jazz Singer,” the first film with spoken dialogue.

“They staked everything they possessed upon the success of the synchronization of picture and sound,” wrote Lawrence Manning Lawlor in Town Talk, a Youngstown-based magazine that devoted an entire issue to the Warner Theatre the week the movie house opened. “Many within the industry predicted utter failure for this venture.”

Instead, the innovation vaulted Warner Bros. to the forefront of moviemaking, “combining good citizenship with good picture-making,” as the studio motto said. But the Warner brothers’ success was not without tragedy. The day before “The Jazz Singer” premiered, Sam Warner died at the age of 40. His brothers decided to memorialize him with an ornate movie theater in Youngstown. They spared no expense, building the foyer to resemble the Palace of Versailles and paying $75,000 for a Wurlitzer organ.

Much like the Warner brothers, at the time of the theater’s opening the city of Youngstown had seen enormous success in a brief period of time, going from the rough-and-tumble town where the brothers took their first steps in the movie business to a center of industry. Its population more than tripled between 1900 and 1930 — up to 170,000 — as scores of immigrants like the Warners and their parents arrived to work in the mills and factories along the Mahoning River.

“With the opening of the new Warner Theatre, Warner Brothers realize a cherished ambition to provide Youngstown with a temple of entertainment comparable to the finest in the country,” wrote Harry Warner in the Youngstown Vindicator the day before the theater welcomed its first guests. “Its formal opening is both a fulfillment and a promise — evidence of our desire and willingness to keep abreast of a progressive city.”

***

Ben Warner came to America because of a lie. A friend from what is now Poland described to the cobbler a land of wealth, so Warner journeyed to Baltimore himself in 1890. He found a hard life but one easier than in the old country, so Warner sent for his family and set up a shoe repair shop.

His oldest son, Harry, a cobbler like his father, ventured to Ohio in 1896, wanting to see William McKinley, who was waging a front-porch campaign for president from his Canton home. While there, Harry — all of 14 years old — was urged to go to Youngstown, then a booming steel and iron production center with many people who needed their shoes repaired. He set up a shop downtown and prospered enough that, eventually, his parents and nine siblings came to join him.

The Warner Theatre opened in 1931 as a tribute to Sam Warner. This photograph is from around 1934. (photo courtesy of Mahoning Valley Historical Society)

Ben branched out, operating a grocery store and butcher shop in Youngstown, and the brothers began to make good on their youthful promise to their mother, recalled 40 years later by family friend Myron Penner: “We’re gonna be millionaires some day.”

Albert, who was two years younger than Harry, sold soap through a company in Chicago, and then operated a downtown Youngstown bicycle shop with Harry. The duo also briefly ran a bowling alley.

Sam, four years younger than Harry and described later on by the Youngstown Vindicator as the idea man of the brothers, worked as a railroad fireman and brought ice cream cones to Youngstown after seeing them at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Even young Jack, 11 years younger than Harry, was working as a carrier for the Youngstown Vindicator, a delivery boy for his father’s butcher shop, and then as a chaser at the Dome Theater, with the stage name Leon Zuardo. He was hired at $18 a week to sing poorly enough to keep audience members from hanging out too long in the theater and taking up real estate that could be used for more paying customers.

Jack wasn’t the only one to catch the show-business bug. Sam was working as a nickelodeon operator at Cedar Point in Sandusky and Youngstown’s own Idora Park. During a trip to Pittsburgh, Harry had seen lines around the block to watch a movie. He wasn’t interested in the films themselves, but he saw an opportunity to make money.

A movie projector came up for sale in Youngstown, along with a copy of the 12-minute, 1903 silent short “The Great Train Robbery,” now heralded as a watershed moment in film history. The cost was $1,000, and Sam convinced his brothers it was an opportunity they couldn’t pass up.

They pooled their money, but were still short, so they looked to their father. Ben pawned the horse that pulled the delivery wagon for his business — as well as his gold watch and chain, one of a few possessions he’d brought with him from Europe. The Warner brothers were on their way.

***

The brothers screened “The Great Train Robbery” wherever they felt like they could get an audience — Idora Park, Steubenville, Warren, Niles (Jack later said that their film empire began in Niles when they took in $300 in one week showing the movie) and into Pennsylvania. They opened their first theater in New Castle, Pennsylvania — calling it the Cascade — with 99 chairs (100 or more would have required a license) borrowed from a nearby funeral home. It was truly a family affair, with Harry handling the books, Sam selling tickets, Albert running the projector and Jack once again singing between showings to chase away the customers.

Eventually, the market for “The Great Train Robbery” dried up, so the brothers set up a film exchange in Pittsburgh where theater operators could share movies they’d bought. The Warners expanded into other film exchanges in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles and eventually decided to make their own movies. They had early success with “My Four Years in Germany,” a film based on a book written by James W. Gerard, the U.S. Ambassador to Germany during World War I, but were one of many companies that had to jockey for position in the movie business alongside the big three of Paramount, MGM and Universal.

Warner Bros. Studios was incorporated in 1923, and two years later, it acquired Vitagraph Studios — a deal that was a testament to Harry’s business acumen and his bravery (he wrote a check for $100,000 before securing any of the needed $4 million in seed money, much of which came from Goldman Sachs).

Meanwhile, Sam was watching Western Electric demonstrate sound that would synchronize with movies. He was immediately taken with the idea, and the company bought the rights to Vitaphone, which functioned basically the same as a record, playing a recording that was synchronized to the film. The following year, in 1926, Warner Bros. debuted “Don Juan,” starring the legendary John Barrymore and filmed with the Vitaphone process. It consisted of some music and sound effects — no dialogue — but the synchronization worked.

“We never dreamed that we would live to see such a performance and above all that we would be parents of such wonderful boys,” Ben and Pearl wrote to Jack after the premiere of “Don Juan.” “When four marvelous boys like you stick together through thick and thin, there is no question but that you will attain all the success you hope for.”

On Oct. 6, 1927, “The Jazz Singer,” the first movie with dialogue, made its New York premiere. None of the Warners were there. They were busy making funeral arrangements.

Sam had been taken to the hospital a week earlier with a sinus infection. It developed into pneumonia, and he died at 3:15 a.m. on Oct. 5 — a day before “The Jazz Singer” debuted, changing movies forever and turning Warner Bros. into a major Hollywood studio.

***

Warner Bros. continued its upward climb throughout the 1930s, offering grittier movies with stars like James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson and a young New York City native named Humphrey Bogart. In fact, Warner Bros. had become known as the gangster studio with its tales of organized crime — a testament to the Warners’ Youngstown roots.

“J. Edgar Hoover once told me that Youngstown in those days was one of the toughest cities in America, and a gathering place for Sicilian thugs active in the Mafia,” Jack recalled in his autobiography. In fact, W.R. Burnett, the author of the book Little Caesar, which became one of Warner Bros.’ early hits, suggested Jack was eager to buy the rights because its main character was a gangster from Youngstown who ascended to the top of the rackets in Chicago.

But family troubles were starting to take their toll. Harry, who had never approved of Sam’s wife, adopted their daughter to raise her as his own, and a series of affairs by Jack led to the disintegration of his marriage to his wife, Irma.

In 1934, Ben and Pearl celebrated their 50th anniversary — in the hospital, after Pearl suffered a stroke. She died the next day.

A little more than a year later, Ben made a trip back to Youngstown to visit his friends and his daughters, who had stayed there. He was playing cards with the same people he played cards with as a cobbler and grocery store owner a generation earlier when he had a stroke. He died a day later at his daughter’s home. Out of respect, the theaters in Youngstown stopped showing movies for two minutes at 2 p.m. the next day.

After his father’s funeral, Jack moved his girlfriend, Ann Page, into his home (he and Irma had divorced earlier that year). They were married in 1936. None of the family attended. Thirty years later, when his autobiography, My First Hundred Years in Hollywood, came out, it made no mention of Irma or their only child, Jack Jr.

***

Although the era following World War I made the Warner brothers, the years after World War II were unkind to them. Potential moviegoers were starting to gravitate toward television — a move that Warner Bros. tried to capitalize on by selling its film library for television use. After revolutionizing the film industry with sound, the studio’s investment in 3-D movies fizzled, and it was 20th Century Fox, not Warner Bros., that came up with the successful new widescreen format known as CinemaScope.

The brothers were getting old, too. Harry was tired of fighting with Jack, and Al had more interest in racehorses than moviemaking. It was time to put the company up for sale. In 1956, the brothers reached an agreement that would allow them to sell the bulk of their stock and retain seats on the board of directors, but give up their jobs.

But Jack cut his own deal. He bought back his shares at the same sale price, and with his brothers out, he was now president of the company. Albert’s family later said he had rage enough to kill when he found out about his brother’s duplicity, and Harry was so apoplectic he had a stroke while reading about the sale at breakfast.

Harry died two years later. “He didn’t die,” his wife Rea said, “Jack killed him.”

Jack was in the south of France and didn’t attend the funeral. Four days later, he was involved in a serious car wreck. His sister Sadie told him it was divine retribution for what he’d done to his brothers. He never spoke to her again and didn’t attend her funeral a year later.

Jack recovered and continued to lead the studio through the 1960s, but the movie industry had passed him by. Powerful studio heads like him were virtually extinct, and he was getting old himself. He sold his shares in the studio in 1966, but retained an office and produced some movies on his own, including “Camelot.” That same year, the studio released “Bonnie and Clyde,” which started a new era of gangster movies.

“Bonnie and Clyde” was also the last movie played at the Warner Theatre in Youngstown, on Feb. 28, 1968. By that time, downtown was no longer the commercial center it once was, and the theater closed. Myron Penner, who’d lived in the Warners’ home when he was a child, maintained his correspondence with Jack through the years and told him about the demise of the theater built as a memorial to his brother.

“Am sorry to hear this,” Jack wrote, “but progress can’t be stopped.”

Prior to the theater’s appointment with the wrecking ball, a Youngstown man, Edward W. Powers, stepped forward with $250,000 to buy the theater and donate it to the Youngstown Symphony Orchestra. The renamed Powers Auditorium remains to this day, restored to its former grandeur as the centerpiece of what is now the DeYor Performing Arts Center. In 2003, a historical marker was placed out front commemorating the Warner brothers.

Albert died in 1967 and hadn’t been involved in the movie studio’s day-to-day operations since its sale in 1956. Jack, the last surviving brother, died on Sept. 9, 1978. He was 86, and his death was front-page news.

“Not bad for a butcher boy from Youngstown,” as Jack said after he finally sold his stock and retired from the company he and his brothers founded.

But it was on the occasion of Harry’s death that the Youngstown Vindicator noted in an editorial how the Warner brothers were the living embodiment of the American Dream: “Here were four boys with no wealth or influence behind them; moreover, they were immigrants and members of a minority religion. In the land of opportunity, they made the most of their chance.”

Related Articles

A First Look at the Ohio-Made Movie ‘Lost & Found in Cleveland’

In this film by Keith Gerchak and Marisa Guterman, an antiques-appraisal television show’s visit brings together a diverse cast of characters. READ MORE >>

20 Movies That Were Made in Ohio

Academy Award-winning tales, lesser-known finds and, yes, even a couple of couple box-office bombs have been filmed in the Buckeye State. READ MORE >>

Seth Breedlove's Search for the Unexplained

The Small Town Monsters founder and filmmaker discusses his love for exploring American myths and lore. READ MORE >>