Toledo Hosted Golf's Longest-Ever U.S. Open in 1931

In 1931, one of golf's four major championships was held at Toledo's Inverness Club and finished with an epic ending that has never been repeated.

July 2016 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of The Inverness Club

July 2016 Issue

BY Vince Guerrieri | Photo courtesy of The Inverness Club

George Von Elm had no margin of error as he marched down the Inverness Club’s 18th and final fairway on July 4, 1931.

One of the great amateur golfers of the 1920s, Von Elm had been carrying a two-stroke lead into the U.S. Open’s last nine holes. That was before the self-proclaimed “businessman golfer,” who spent his days working in finance, three-putted on 16. He would need a birdie on the Toledo course’s final hole to catch Billy Burke and force a tie.

The weather that Fourth of July was brutal, as it had been for days, with temperatures soaring into the triple digits. The fact that the 6,529-yard course was the shortest to host the U.S. Open in a decade didn’t help the situation much. The former cornfield had limited shade and plenty of high grass in the rough, making the long, hot days of competition even longer for the tournament’s 144 players.

Burke — an American professional golfer whose unorthodox swing was due to a mill accident that claimed two fingers — and Von Elm had been chasing each other for three days and 71 holes as the rest of the field wilted.

Now, it all came down to 18. Von Elm’s drive landed about 75 yards from the green, and his second shot put him a dozen feet from the hole. After flubbing an easy, 2-foot putt just two holes earlier, those in attendance wondered if he could shake off the miss.

Von Elm stepped up and tapped the ball, his eyes following as it rolled across the green and then, finally, disappeared beyond the edge of the cup. He nearly fell over as the crowd converged around him. After 72 holes of play, the U.S. Open was tied at 292 strokes.

A tie at the end of the U.S. Open was not an unusual occurrence. In fact, it had become a tradition in odd-numbered years dating back to 1923. But unlike other golf tournaments of the time, the U.S. Open didn’t have a sudden-death playoff. Instead, the tied players returned the following day for 36 more holes of golf. It had last happened in 1929, when Bobby Jones, the greatest golfer of his era, won the playoff round by a dominant 23 strokes.

But what was about to happen at the Inverness Club during the 48 hours to follow would prove to be unprecedented. It has also never been repeated.

***

During the first half of the 20th century, the idea of professional golf was generally looked down upon. Although the Professional Golfers’ Association was founded in 1916, it wasn’t until the 1940s and 1950s that professional golf began garnering the status it holds today. During the 1930s, playing on the amateur circuit was the pinnacle of the sport. The only problem was there was no money in being an amateur.

Von Elm, a native of Salt Lake City, discovered that firsthand during the 1920s. He was ultimately suspended from the amateur circuit for a year in 1922 for taking money to cover his travel expenses, which he estimated topped $10,000 annually.

In 1930, he renounced his amateur status, saying, “I propose hereafter to play golf in such open events as I choose and on such occasions gamble my skill against the prize money.” He dubbed himself the “businessman golfer” and it seemed to work. In 1931, he was golf’s leading moneymaker, earning $7,957.50 in prize money prior to the U.S. Open, or the equivalent of about $116,000 today.

But odds-makers had Tommy Armour, who had won the British Open by a single stroke a month earlier, as a 5-to-1 favorite going into the 1931 U.S. Open. Burke, who hailed from Naugatuck, Connecticut, was also regarded as a strong contender and given 10-to-1 odds. The field also included Walter Hagen, who would go on to become the first professional golfer to top $1 million in earnings from the game. He was flamboyant — showing up at tournaments in a tuxedo — but also supremely talented, with two U.S. Open and four British Open titles to his name by the summer of 1931.

Soaring temperatures led to small crowds of spectators for the 1931 U.S. Open. (photo courtesy of The Inverness Club)

The legendary Bobby Jones was also at the Inverness Club for the 1931 U.S. Open, but only as a spectator. After winning the U.S. Amateur, British Amateur, U.S. Open and British Open in 1930 — an unprecedented accomplishment that came to be known as a Grand Slam — he retired from competition. An Associated Press story from the time noted that he was interested in starting his own private golf club and making instructional films for Warner Brothers.

Jones’ first U.S. Open appearance had been at the Inverness Club in 1920, where he finished four strokes off the lead. Although he was moving on from competitive golf, he couldn’t stay away. His feelings about the club were highlighted in the 1931 U.S. Open program: “It is a place to which one loves to return, and I am very happy to be back here this summer.”

***

The temperature was already above 80 degrees when the 1931 U.S. Open began at 8:30 a.m. on July 2 and only climbed higher as the day went on. It kept the usual crowds away, although Bobby Jones had a small following of reporters and fans trailing him, including Ohio Gov. George White, who had stopped by the Inverness Club while traveling back to Columbus from the Ohio city of Napoleon.

White remarked on the heat to a reporter, but offered no prediction for victory before adding, “Now if Bobby here were playing … ”

Jones’ absence from the field and the stifling temperatures resulted in a small gallery of spectators — around 4,000 — that first day. The initial round of play ended in a four-way tie for the lead between Eddie Williams of Cleveland, Charley Guest of New Jersey, Herman Barron of New York, and Mortie Dutra of California. Burke was two strokes behind the leaders, while Von Elm was four back.

Von Elm got into a groove on the second day though, making five straight birdies and taking the lead. Over the course of the round, Burke moved into second place, tied with Williams and a stroke behind Von Elm. But the largest crowds on the second day — estimated to be around 2,000 — were following Hagen, who finished the round two strokes behind the lead. (By the second day of the tournament Bobby Jones had left, heading to Cleveland to watch a prizefight between boxers Max Schmeling and Young Stribling in the first event ever held at Cleveland Municipal Stadium.)

The third and final day of regulation play featured 36 holes rather than 18, and the field of 144 golfers had been winnowed down to 63. But it quickly turned into a two-man race between Von Elm and Burke, with Williams fading from contention during the first 18 holes.

But the big news of the day was the collapse of odds-on favorite Tommy Armour, whom Grantland Rice, the dean of American sportswriters, called “the most dangerous man in the field” prior to the start of competition. Armour finished the day 23 strokes behind Burke and Von Elm.

With Von Elm’s incredible July 4 birdie on the final hole and the promise of a 36-hole playoff round the next day, Rice’s words from the 1931 U.S. Open tournament program carried even more weight: “Complete proof that anything can happen in an Open championship was never better shown than in the tournament held at Inverness eleven years ago,” Rice wrote in regard to the 1920 tournament. “… Open championships are full of stories that prove how quickly these amazing changes and reverses can take place.”

Those words would prove all the more prophetic in the days to follow.

***

On the morning of Sunday, July 5, 1931, Burke and Von Elm began their 36-hole playoff to determine a winner. The sweltering temperatures were back and only around 2,000 spectators showed up.

In the morning, Burke opened up a four-shot lead on Von Elm, but by the time the two broke for lunch after 18 holes, his lead had been cut to two. An afternoon rain helped tame the temperature a bit as Von Elm birdied four straight holes to take a two-stroke lead, which he then promptly gave up.

Burke dropped a 15-foot putt on 17 and held a one-stroke lead going into the final hole. It looked like it might be over. Von Elm would once again need to birdie on 18, as he did just 24 hours earlier to push he and Burke into a second playoff round of 36 holes the following day. It seemed unlikely. But then Von Elm did it, and in almost the exact same way as he did a day earlier: with a smashing drive, a perfect pitch to the green and a spot-on putt.

“Apparently they are going on forever,” Rice wrote in his column. “After the most sensational 36-hole playoff in the history of golf, they are still tied up in a two-ply Gordian Knot at 149 strokes each. There were enough fireworks in this contest to make the fall of Pompeii look like a single Roman candle.”

***

As the second 36-hole playoff round opened on Monday, July 6, the 1931 U.S. Open became the longest in tournament history. The United States Golf Association dropped the admission price to $2 for the day — or just $1 for only the final 18 holes — and the fairways were lined with as many as 7,000 spectators.

In the morning round, Burke three-putted the first hole and spent most of the second hole in the rough, giving Von Elm an early lead. But Burke calmed down and was only one stroke behind his rival after the first 18 holes.

As the afternoon stretched on, Burke’s one-stroke lead widened to two, and it was clear the strain was starting to get to Von Elm. Before attempting his putt on the final hole of the round, he demanded complete silence from the crowd.

Burke was a bit more relaxed. He missed his first putt on 18, but any drama it generated was short-lived. He buried the second easily, claiming victory by a single stroke on the final hole of the second playoff round. The longest-ever U.S. Open was over. The final tally: 144 holes played, 9 pounds lost by Von Elm and 589 strokes to win by Burke.

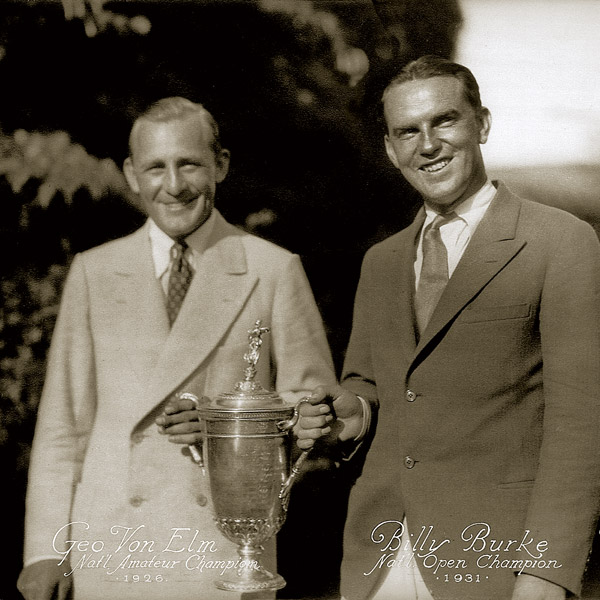

George Von Elm (left) and Billy Burke post with the 1931 U.S. Open trophy at The Inverness Club. (photo courtesy of The Inverness Club)

Such a marathon U.S. Open would never again be repeated. The following January, the USGA decreased the playoff round to 18 holes. In 1953, it further changed the rules to adopt a sudden-death playoff if the first playoff ended in a tie. Also, in 1932, the U.S. Open was moved from July to June, to avoid temperatures like those at what had come to be called “the Inferno at Inverness.”

Burke was paid $1,750 for the tournament itself: $1,000 for winning and $750 for the playoff. Von Elm got $750 for the tournament and $250 for the playoff.

As summer turned into fall, Von Elm and Burke would go on to play a series of exhibition matches, but first, Burke and his wife, Marguerite — whom he met at a dance at the club he worked at in Connecticut and who had watched the entire U.S. Open — were off to Niagara Falls. They’d married a year earlier and were taking a belated honeymoon.

The respite was well deserved, as Burke himself remarked after his victory: “I won the national Open golf championship, but I earned it.”

Related Articles

Visit the Ohio Graves of 5 U.S. Presidents

Seven presidents were born in Ohio, and another called the state home before being elected. Connect with that history by visiting the final resting places of the five who are buried here. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=c7bfb738_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

3 Ways to Celebrate Ohio Statehood Day in 2025

Happy birthday, Ohio! Celebrate 222 years of the Buckeye State this week in both our current and former capital. READ MORE >>

Visit This Gothic-Style Temple in Lake County

The northeast Ohio community of Kirtland played a pivotal role in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. READ MORE >>