Ohio Life

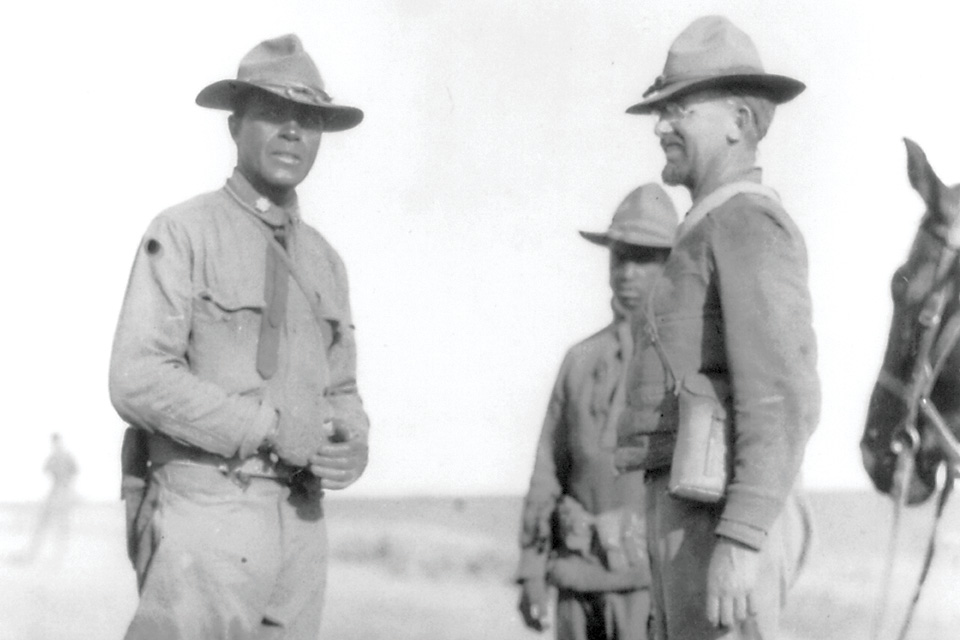

The Life and Legacy of Col. Charles Young

Charles Young was the most highly decorated African-American military officer of his time, the first black U.S. National Park superintendent and a professor at Ohio’s Wilberforce University.

Related Articles

See ’Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects’ in Lancaster

The Decorative Arts Center of Ohio hosts an artifact-focused exhibition that tells the story of our state through a collection of family keepsakes and iconic inventions. READ MORE >>

Historic Marker Installed at Home of Orville Wright

Hawthorn Hill, the Oakwood home where aviation pioneer Orville Wright lived with his sister and father, now bears a new marker celebrating its place in American history. READ MORE >>

Experience Spiegel Grove’s Civil War Winter Camp

History buffs can check out 19th-century camp life, see a brass band on horseback and even take a spin in a Model-T at this immersive fall event. READ MORE >>