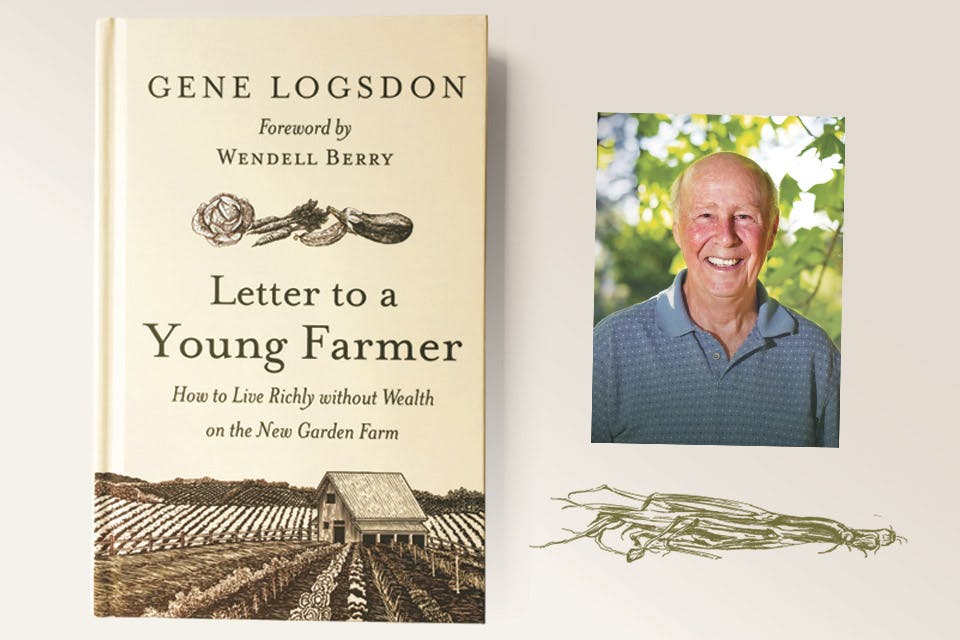

Gene Logsdon’s Last Book Shares His ‘Letter to a Young Farmer’

Gene Logsdon was both philosopher and farmer, writing more than two dozen books and countless columns during his long career. Here, we share wisdom from his final book, ‘Letter to a Young Farmer’

March 2017 Issue

BY Jim Vickers | Gene Logsdon photo by Ben Barnes

March 2017 Issue

BY Jim Vickers | Gene Logsdon photo by Ben Barnes

Gene Logsdon referred to himself as a “contrary farmer” and spent decades proving it by writing books and columns that offered his straight-talk perspective on agriculture and rural living in the United States.

He penned a column for the Carey, Ohio, Progressor Times and wrote a popular blog, but his work also appeared in Farming Magazine, The Draft Horse Journal and, for a period of time, Ohio Magazine. All the while, Logsdon and his wife, Carol, tended to their farm in Upper Sandusky.

In the 1990s, Logsdon began working with book editor Ben Watson of Vermont-based Chelsea Green Publishing, which published his 1995 collection of essays, The Contrary Farmer, as well as the books that followed.

“He was never interested in getting a big [book] advance, or any kind of advance really,” recalls Watson. “Half of the time, I had to convince him to take any money because I thought it was better to do it that way.”

Often what would happen, Watson says, is Logsdon would write an entire first draft before submitting a single page for review. That’s how it happened with his final collection of essays, Letter to a Young Farmer: How to Live Richly without Wealth on the New Garden Farm, which was finalized just a few weeks prior to Logsdon’s death in 2016.

In it, he addresses the rise of garden farmers and their small-scale operations that aim to connect with the land and the living things that grow on it without regard for the financial reward that drives large-scale agriculture. It’s a way of life that favors staying close to home and living with mindful simplicity over buying into the rampant consumerism of a modern culture that wants us to spend and accumulate more and more.

“That kind of economy, [Logsdon] was totally uninterested in,” says Watson, “and he knew that there are lots of people out there who are similar, including a lot of young people.”

His essays in Letter to a Young Farmer are infused with wit and an insight that can only come from someone who has spent as many years as Logsdon did working in his fields and caring for the animals in his barn.

But rather than timeworn tales, the collection of essays serves as an inspiration. Even for those of us who aren’t able to embrace the garden-farming lifestyle, Logsdon’s writing makes us want to. He deftly balances reverence with reality as he shares his ideas about where farming fits into present-day society and its role in our collective future.

From his perspectives on robotic farming to made-in-the-laboratory steaks to the connective power of farmers markets, Logsdon’s words in Letter to a Young Farmer crackle with authenticity and wisdom. On the following pages, we share some of our favorite passages from the book, which offer a glimpse into not only Logsdon’s wonderfully contrary nature, but his respect for the land and our connection to it.

----

Agricultural experts will no doubt repeat the commonplace advice that beginning farmers have been hearing for a century or more. The advisors mean well. It is just that trying to tell someone how to succeed in farming is about like trying to tell someone how to succeed as an artist, writer, or musician. There are many ways, but the rules all start with the word “if.” (Chapter 1, “No Such Thing as ‘The American Farmer’”)

The biggest mistake in getting into farming ventures is the assumption that, if you know how to do it and follow the know-how strictly, you will succeed. (Chapter 2, “Farming Is All About Money, Even When It Isn’t”)

Young people tell me that they can’t afford to buy a little piece of land like Carol and I did. Today’s land prices are too high, they say. But land prices are always too high. We bought our twenty acres in 1974 for $700 an acre and thought that was too high. Later we bought ten more for $2,000 an acre, and I know that was too high. When pioneers were paying $5 an acre for homesteads, they thought that was too high. (Chapter 2, “Farming Is All About Money, Even When It Isn’t”)

Maybe farming isn’t an economic process that is supposed to make money. What if food production should be an activity that nearly everyone has to be involved in, like cooking or taking a bath? (Chapter 3, “The Economic Decentralization of Nearly Everything”)

Critics often tell me that my idea of feeding the world with small-scale garden farms is naïve, like saying we could supply everyone a homemade car. But a car requires all sorts of overhead money and artificial outside inputs, while food grows mostly on the ubiquitous gifts of sunlight, soil fertility, and rain. (Chapter 3, “The Economic Decentralization of Nearly Everything”)

The new garden farming movement is being driven by upscale restaurant chefs, by the flocks of people who frequent farmers’ markets looking for fresher food, by a growing number of people who are suspicious of regular commercial food, and most of all by a millennial generation that seeks a different philosophy to live by than what industrialism offers them. (Chapter 4, “The Ripening of a ‘Rurban’ Culture”)

Sitting in a quiet barn, surrounded by your animals, you feel you are in a citadel of security, safe from the onslaughts of money markets, weather, and human madness. There is an independence here and a pride that gives a person a kind of satisfaction not common anymore. (Chapter 5, “The Barns at the Center of the Garden Farm Universe”)

You know most or all of your animals by name. Curlyhead needs to be penned tonight because she is about to have lambs. You learn how to play midwife if necessary. Make sure the rooster, Trump, is in the coop before you close up, or he will be crowing in your bedroom window at daybreak. Give Shorthorn, the steer, a little more grain tonight, and don’t let Whiteface push him away from it. […] Make sure that little pigs and lambs are all back with their mothers before you go to the house. (Chapter 5, “The Barns at the Center of the Garden Farm Universe”)

Orphan, bottle-fed lambs are a pain and not very profitable, but we could almost always find an acquaintance who wanted their children to have the experience of raising a farm animal. Nothing can captivate youngsters like bottle-feeding a lamb. The lamb becomes a loving pet. As I have said, we put a diaper on one and let it have the run of our house. Very entertaining. This can be a way another new shepherd gets started. Or the lamb can become a 4-H fair project. The experience almost always ends in tears when the child must sell the lamb or see it turned into lamb chops, but that also can be a useful lesson in what life is all about. (Chapter 6, “Backyard Sheep”)

Women have always played the key role in farming, of course, but they have seldom been given credit for it publicly or historically. Farming is a man’s world, American culture wants us to believe, and as is true of all culturally treasured myths, no amount of plain everyday evidence to the contrary matters much. (Chapter 9, “The Rise of the Modern Plowgirl”)

Hard physical work always seems easier with two people involved: “Many hands make light the task,” as the old saying puts it. When I am hoeing corn, it makes all the difference in the world when Carol’s hoeing toward me from the other end of the row. Instead of inching along growling about the damned flies and gnats, the damned hoe that needs sharpening, the damned sweat in my eyes, and the damned weeds that would have been easier to hoe out last week, I’m thinking, “Oh, great, I only have to do half the row.” (Chapter 10, “Finding and Keeping a New Age Farm Partner”)

The news these days is all about how cars may someday drive themselves and how tractors already can. Am I supposed to be impressed? A hundred years ago, everyone had a self-driving car. It was called a horse and buggy. If you fell asleep at the reins, you could depend on a good buggy horse getting you home safely. (Chapter 11, “Big Data and Robot Farming”)

For those who keep backyard chickens, this is important information: A well cared for bluegrass / white clover lawn can supply most of the hens’ ration through most of the year, even in winter when snow does not cover the ground. Also, when you mow your lawn, let the clover dry like you would when making hay. Then rake up the dry clover and store it out of the weather to feed hens in winter. (Chapter 14, “Pasture Farming as Part of Garden Farming”)

If you are buying apples from the grocery store, rightly enough you expect that they aren’t blemished or wormy. But with free fruit, a bit of imperfection is not so objectionable. While peeling an apple, cutting away bad spots is only a little more work. So in a way it is because of money that a whole bunch more money needs to be spent unnecessarily, spraying fruit to keep it free of blemishes. (Chapter 15, “The Wild-Plant Explorers”)

Farmers’ Markets are a natural economic outgrowth of urban society and probably ought to be called city markets. They have been around as long as towns and cities have existed and are one of the few economic inventions that have continually resulted in peace and friendship between rural and urban societies. All segments of society mingle at a market: rich and poor, theist and atheist, liberal and conservative, artist and scientist. At a farmers’ market, you might catch a Tea Party Republican smiling at an Obama Democrat, both carrying a bag of new potatoes. (Chapter 18, “The Resurrection of a Really Free Market”)

It’s fun to eat truffles and caviar and antelope jerky occasionally if you’ve got the money, just like it’s fun to buy an expensive English hoe, even though a cheaper one will do the job. It is great to be able to pay five dollars for a dozen organic, blue Aracauna eggs or a box of flour made of dried, roasted crickets. But some place along the line, there must be attention paid to producing wholesome tasty foods that are also affordable for most people and require less carbon emissions to bring to market, not more. (Chapter 19, “Artisanal Food in the New Age of Farming”)

When “well-meaning” people today deplore all the pain and suffering involved in raising and slaughtering livestock, they seem to ignore the fact that even more grisly pain and slaughter occur in the wild. Lions and tigers pull down zebras and wildebeests and eat away at them even while they are still alive. Wolves and wolverines chase a deer to exhaustion and then tear it apart bite by bite. Hawks rip squealing rabbits apart with their beaks and talons. Rarely in the wild does anything die of old age. (Chapter 20, “Why Fake Steak Won’t Ever Rule the Meat Market”)

Education has failed in this regard. We no longer teach children the reality that they learned just by living on a farm a few generations ago. Nature is one huge dining table around which all life sits, eating while being eaten. (Chapter 20, “Why Fake Steak Won’t Ever Rule the Meat Market”)

Growing up on a farm, I knew so many moments of utter peace when I listened to cows munching hay at night, or watched the sun come up out of the fog when I was already in the field, or sitting by the creek under a shade tree for a noon break watching the water flow by, or listening to the corn grow on a July night, or the sound of rain falling on the roof after dry weather. (Chapter 21, “The Homebodies”)

No matter how many times I walk or work the same land, there is always something new to discover and turn into even more tranquility. That is my reward, my destiny, my life. (Chapter 21, “The Homebodies”)

To learn more about Letter to a Young Farmer: How to Live Richly without Wealth on the New Garden Farm, visit chelseagreen.com.

Related Articles

2025 Ohio Book Award Winners Announced

These annual awards from the Ohioana Library honor Ohio-centric books. They will be presented Oct. 15 at the Ohio Statehouse. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=63bdb638_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

Enjoy Family Fun on the Farm in Lake County

Visit Lake Matroparks’ Farmpark on June 21 and 22 for Dairy Days, where kids can milk a cow, ride a pony and more. READ MORE >>

Ohio Farmer Lee Jones Appears in a New TV Series

“The Chef's Garden” from Rachel Ray and International Content’s Free Food Studios is set to premiere on the A&E network Jan. 27. READ MORE >>