Ohio Life

America's Last Great Train Heist

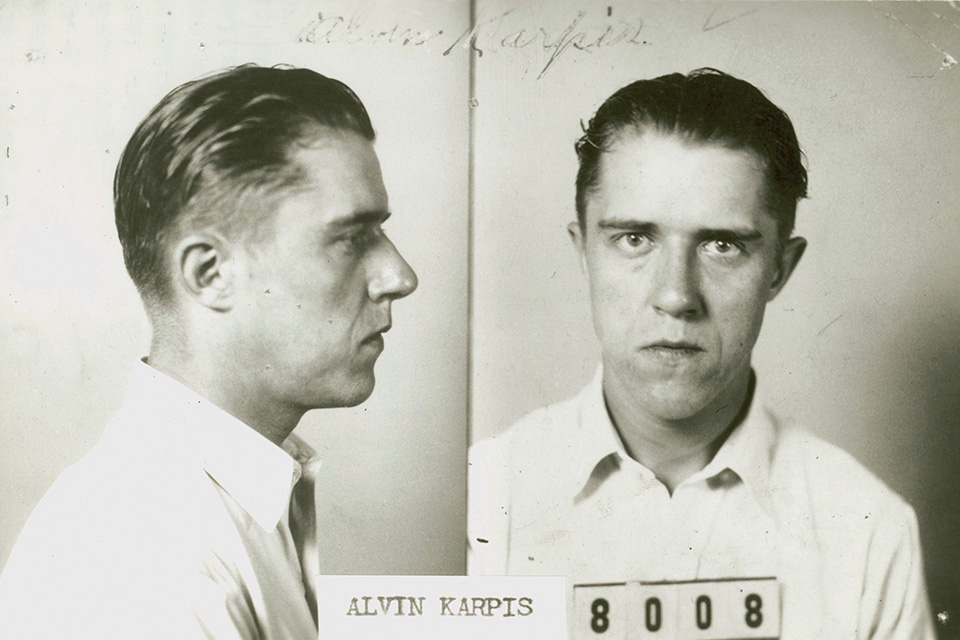

In November 1935, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis and his crew robbed a mail car in Garrettsville, Ohio, scoring a bunch of cash and making a daring escape by both car and airplane.

Related Articles

Visit the Ohio Graves of 5 U.S. Presidents

Seven presidents were born in Ohio, and another called the state home before being elected. Connect with that history by visiting the final resting places of the five who are buried here. READ MORE >>

.jpg?sfvrsn=c7bfb738_5&w=960&auto=compress%2cformat)

3 Ways to Celebrate Ohio Statehood Day in 2025

Happy birthday, Ohio! Celebrate 222 years of the Buckeye State this week in both our current and former capital. READ MORE >>

Visit This Gothic-Style Temple in Lake County

The northeast Ohio community of Kirtland played a pivotal role in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. READ MORE >>