Travel

3 Ways to Explore Black History

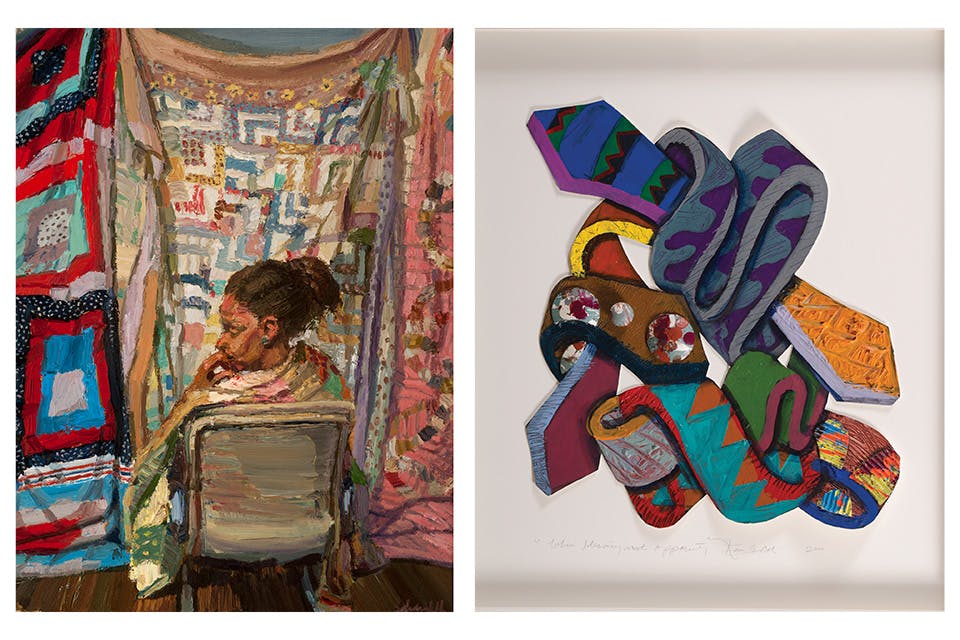

These Ohio institutions share insight and inspiration as they showcase stories and artwork that highlight the African American experience.

Related Articles

See “Botanical Fantastical” at Pyramid Hill Sculpture Park & Museum

Experience this nature-focused art exhibition on display at this Butler County attraction’s Gallery Museum at Pyramid Hill through July 27. READ MORE >>

See ‘Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike’ in Cincinnati

Explore the evolution of bicycle design at the Cincinnati Art Museum during “Cycle Thru! The Art of the Bike,” on display from April 4 through Aug. 24. READ MORE >>

Celebrate Legendary Women at These 5 Ohio Museums

Visit these sites that honor individuals who left an indelible mark on history, from a pioneering suffragist to a famous sharpshooter to a literary icon. READ MORE >>